Interview with a panhandler

Q & A with my brother Phil, on the way to his intersection.

Nearly 40 years ago, on the first night of my five-week high school journalism summer camp experience, an instructor began detailing an assignment all of us teens were to pursue shortly: an interview of a “panhandler.”

Unfamiliar with the term, I began pondering what questions I should ask someone who—what? Sold pans on the side of the road?

My train of thought was interrupted when the speaker revealed the panhandler feature was all in jest. We’d have plenty of assignments, she declared, but interviewing a person who asked for money or food in public would not be one of them.

I felt deflated, disappointed. Even back then, only a year into my journalism journey, I was ready to interview just about anyone.

Ten months ago, this memory came to mind as I helped my brother Phil move from one studio apartment to another in Chicago. Phil has led an extraordinary life, as I’ve noted in previous columns. For the past five-odd years his income has flowed almost entirely from panhandling.

After helping him move in, I drove him to the busy intersection in the Chicago suburbs that he’s staked out the last few years. On the way, I asked if he’d be open to an interview focusing on his experiences as a panhandler—and my sharing its contents publicly.

Phil agreed immediately. I pressed “record” on my smartphone’s audio app.

Below is a transcript, only slightly edited for clarity, of what came next on the afternoon of Friday, April 28, 2023.

MB: So, Phil, when someone drives up into an intersection—they see someone, maybe it’s you, more likely it’s somebody else. What can they do to help?

Phil: Put your window up and wave. Because some of these panhandlers want the window down, ‘cuz they’re going to harass you. A lot of them are crackheads. Not everyone is a crackhead but go `safety first.’ Put your window up, smile and wave. Or crack it a little bit and put a dollar bill through the window if you have it to spare.

But when they see the window going up, panhandlers get pissed. They’ll stand in front of your window with a sign.

MB: They’ll feel offended?

Phil: Yeah but rolling up your car window is a natural thing to do. People have children in the car, or they have belongings. A lot of [motorists] go right for their console to make sure there’s no money or something important showing because they’re afraid someone’s going to whip open a door.

MB: When you approach a car, what’s going through your mind? Do you try to make eye contact?

Phil: No, I don’t make eye contact. I wave and look at the clouds, I look at the buildings around me. I’ll wave every few cars. If a window’s open, I never look in. People have their privacy and I don’t step on that. If they want to give me something, they’ll yell at me.

MB: Has that been your approach from the beginning?

Phil: Yes. Oh, yeah. It’s bold to panhandle in the first place. In the beginning, I wouldn’t get off the sidewalk. It’s humiliating. It’s really painful when people do give me money.

MB: Take me back to that time when you first did it.

Phil: When I first did it? Oh my God. I couldn’t believe that people were actually giving me money and I felt bad every time.

MB: Where were you?

Phil: That was Maywood, a few years ago. Then I went up to Harlem [Avenue in Oak Park, near the Eisenhower Expressway] and there was somebody on every corner. I just felt so bad for these people in the car. I tried to make it comfortable for them.

MB: This was just before COVID hit, this was like four years ago. I know it’s painful for you to think about this, so I appreciate you sharing. What was happening that you were just like, `I need this, because if I don’t get X number of dollars, I’m going to get dope sick.’

Phil: I had injuries and COVID kept [handymen like me] out of their homes—they didn’t want anyone. I was making over a bathroom for one of my bosses and the President [Trump] got sick and this client just said `No—nobody’s coming into my house.’ He had kids and I understood it.

It was winner takes all, every man for himself, you know? You’ve got to get by on 5 or 10 bucks, do it. I didn’t want to go stealing or do anything illegal. If you sat out there eight hours, you could make 20 bucks—that would get you through.

MB: You’ve often said to me that it’s humiliating every time you do it…

Phil: It’s embarrassing, humiliating. The one good thing about COVID was the masks. I could wear a mask and hide. Because sometimes one of my clients, or bosses, would drive by and see me and with a mask, I could hide—I could feel like I was hiding. But they would recognize me anyways, you know? They’d stop and give me a few bucks.

MB: As you approach the intersection, are you looking to make sure there’s nobody else at that intersection?

Phil: Well, yeah, I hope that doesn’t become an issue. But I always have a backup. I can suffer a little more and go a couple miles away or I’ve got a stash [of heroin] at my house, just in case, of course.

But I go up there slowly, timidly, gently. I give thanks and praise.

MB: You give thanks and praise. The biggest amount you’ve ever gotten is how much?

Phil: A woman gave me 100 dollars one time.

MB: And what did you say—or did you even know she did it right away?

(Overcome with emotion at the memory, Phil shakes his head as he tears up. I pause the recording for a minute before we resume.)

MB: OK, we’re back on. So, you just needed a moment there.

Phil: A woman one time gave me 100 dollars. And all these other [panhandler] guys, they brag about it [when they get a large sum] … (Phil begins to cry again. Moments later, his voice is choked with emotion as he resumes.) It made me feel like shit.

(I pause the recording again; Phil needs time to collect himself.)

Phil: Regularly like if you’re out there five days, three of those days, if you’re out there three or four hours, you’ll get a 20-dollar bill. When I hit 60 dollars, I stop—I walk away. I’m just one person. I’m not feeding children.

MB: It’s weird—it’s this real tension you have: The more someone gives you, the worse it makes you feel. The more you appreciate it too, but you feel worse than if they gave you 50 cents.

Phil: I like change. When they give me change (Phil’s voice chokes up), I jump for joy. When they give me a 10-dollar bill or a 5-dollar bill, I feel bad.

MB: Right. Is it that you feel guilty--like you didn’t work for it?

Phil: No, I feel like they’re taking food out of someone’s mouth.

MB: But logically speaking, nobody would do that if it meant they couldn’t feed their family that day.

Phil: They do it because they’re just trying to help. But you can tell that they can’t really afford it, but they do it anyways.

I share a recent story of giving to another panhandler, including how he responded in gratitude.

Phil: I show too much gratitude. People look at you funny. It’s best just to say, `Thank you, sir. Thank you, ma’am.’ What you don’t want to do is say, `Thank you, sir’ to a woman. (Laughs)

MB: So, `thank you’ is the safest…

Phil: I don’t really look at people or inside their car. That’s their business and sometimes you mistake a gender, you know?

MB: What are some do’s and don’ts—for you, your code.

Phil: Do put your mind on something pleasant and look at the buildings around you and think happy thoughts. If they’re going to help you, they will. If they want to, they might. If they don’t want to, they won’t.

MB: It sounds like you’ve surrendered to acceptance of whatever…

Phil: Right, you know? You just keep moving on. You can go three hours and not make a dime, and all of a sudden a group of cars comes in and it’s like, `Holy…’ All of a sudden you get 20, 30 dollars.

In the next hour, you get like 60 dollars. Just get inside of yourself and…[recognize] this is my fault. I’m here because of me.

MB: It’s interesting you have a certain mindset of thinking happy thoughts, trying to put yourself in a good state of mind.

Phil: Right. People can sense that. They know that. They know when somebody is desperate.

I’ve come up on cars that give me a few dollars. When I start coming back to the top of the road, they want to give me more. I say, `No, no, no. You already gave me. Thank you, though.’ And they’ll say, `No, no, please take it.’

One guy gave me three pennies. I was grateful. I said `thank you.’ Because that’s what one of my signs says, `Anything is a lot.’ My other sign says, `Help is hope.’

MB: Do people ever ask to pray for you?

Phil: Oh, yeah. They say, `What’s your name? We’re going to say a prayer for you.’ And I say, `What is your name?’

I do—I pray for them later. I don’t tell them I’m going to pray, because everyone says it, but these drivers—yeah, they ask you for your name and they give you a card with a picture of Mary or Jesus on it. They really care.

MB: You walk a lot. You think seven miles a day, maybe?

Phil: Eight. Nine, after the trains and everything else. With a bad knee and a bad hip.

MB: Bad knee, bad hip, all sorts of other injuries over your life, including currently fractured ribs and wrist.

Phil: One rib broken right now.

MB: What keeps you going? What keeps you motivated? I’m driving you out here now. You don’t have to do this today. I could give you money.

Phil: No. My habit is not your problem.

MB: Yup.

Phil: I need and I always have taken care of myself. There’s been times when I’ve upset people when I make my problem theirs.

MB: Well, six or eight years ago, you’d ask for 10 or 20 bucks and I’d loan it and you’d give it back and there was this back and forth, remember that? So that was an issue—you’d always give it back, but it was just this gnawing thing…

Phil: Not always. But you know, I’ve got an option. I could go to treatment. But every time I do, I get that itch. I think basically I’ve got nobody counting on me. I don’t have children, I’ve never married, which I think is by the grace of God.

MB: So you’re about to turn 57. How much longer do you think you can do this physically? Not that you want to, necessarily.

Phil: Realistically…33 years. I could keep this up for another 33 years. I’d be 100.

MB: You’d be 90.

Phil: 67, 77, 87…Forty-three years.

MB: Really, you think you could do this until you’re 100?

Phil: Yeah…yeah. Your body gets used to what you put in it. It’s when you stop doing it, you have difficulties. Jerry Garcia, for instance. He went to a clinic to beat heroin, and that’s where he died. It’s such a stress on the system, it killed him.

MB: So what does a good day look like? What’s your ideal day?

Phil: Not hurting anyone…An ideal day is I don’t upset or hurt anyone. Maybe I help a couple people along the way, and of course I have my needs taken care of, which is only 22 dollars, plus bus fare and food.

I reflect on his situation compared to two years ago, when he was homeless before checking into a 30-day drug and alcohol rehabilitation program.

MB: You’re in a better situation now. You have a place to go back to and sleep…How do you feel about it?

Phil: I’m bored. Now I’m bored. I’m so grateful. I’ve got to find things to fill my days now—hobbies, I love movies, I love music, fishing. I need to fill my time with something exciting because life like that was not boring and that’s the worst thing a person can be is bored.

MB: I’ve heard you say to me in the past it helps you feel alive, the adventure: How do you get through the day?

Phil: Yeah. You sleep well when you struggle through a day.

MB: Do you kind of feel like, in your own way, you’re the star of your own movie?

Phil: (Laughs) Yeah, I do, actually. That’s funny. I do. I’m afraid to tell it, though. I don’t think that a paper could hold it.

MB: What kind of movie is it do you think? Is it adventure, suspense, horror, comedy? It’s all of those.

Phil: It’s mostly funny. It’s funny that I’m still here. (Laughs)

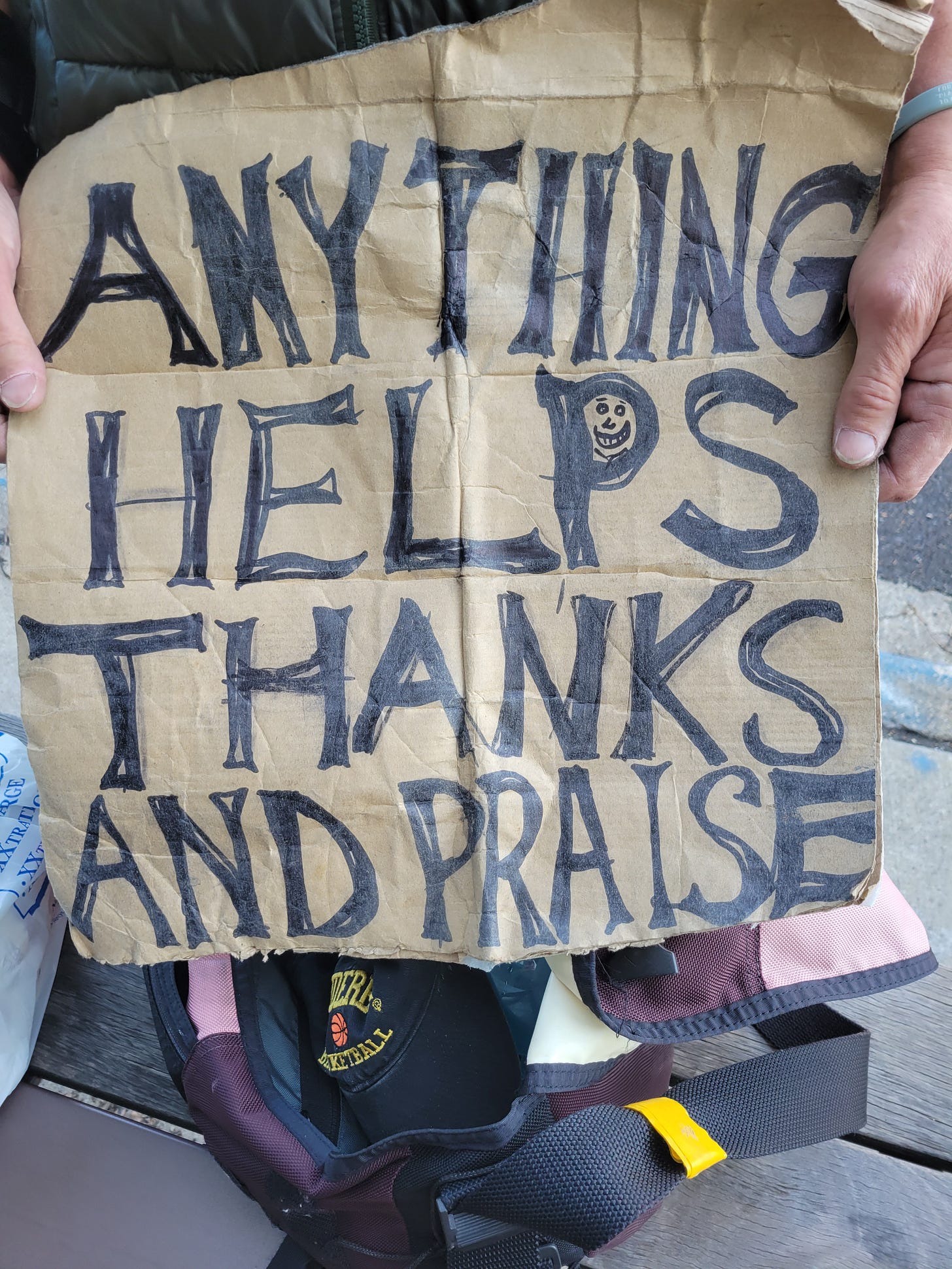

At this point, we’ve reached his intersection — if it’s not the busiest in all of Illinois, it’s certainly close. Our interview is over. As Phil embarks on his shift, I snap this photo, below.

For new readers: Over the past 10 months, I have written over a dozen columns about Phil and my relationship with him. Here’s the first in-depth piece:

Brother Love

On Sunday, my brother Phil’s 57th birthday, I helped him move 10 miles from a subsidized apartment on Chicago’s North Side to another one in the South Loop. Without the intervention of not-for-profit organizations dedicated to combatting homelessness, I don’t know if Phil would still be alive. But I have little doubt he’d be experiencing the homelessnes…

The other thing that strikes me is that your interview, both in terms of the job you did listening and the questions that you asked, was exceptional. You made him look good not because you spun but because you guided.

Tell Phil he came off great. I found zero BS in his answers, and amazingly, no anger. Yes, the star of his own movie. Even before I got to that point, I was thinking someone could use his character as inspiration for a first-person novel. I think of characters termed unlikely heroes, such as the boy in "The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time." He had that same monumental daily struggle.