A Living Eulogy

A few weeks before Father's Day 2008, my dad died. Thanks to a persistent editor, I told him what he meant to me through a column.

Fifteen years ago, I tried ducking one of the hardest tasks of my life. It came masquerading as a journalism assignment.

Transitioning by the seat of my pants from journalism to a suddenly thriving public relations practice, the chain of events began with an e-mail from the editor of a Florida parenting magazine. She invited me to write a Father’s Day column.

A year earlier, just getting my business off the ground, I would have leapt at the chance. But at this point, I had a hectic schedule, which I pointed to in declining the assignment.

While I truly was busy, here’s the deeper truth: I was overwhelmed by the weightiness of figuring out what to write about Dad. Without sorting through it all, I really didn’t know what I thought or how I felt about him and our relationship.

Safely steering clear of that messiness, I moved on to my laundry list of simpler to-dos. Then, to my astonishment, the editor, Michelle Liem, urged me to reconsider.

This was quite the role-reversal. It has typically been the editor saying “thanks, but no thanks,” with an occasional “yes” sprinkled in between the steady stream of rejection.

Now here I was being pursued, despite never previously writing for the publication. Why?

After reaching out to Michelle this week in search of an explanation, she kindly dug through her files, including our original correspondence that included four parenting essays. The short answer: she enjoyed my writing.1

To this day, I am so grateful she stuck with me.

Three months earlier, when we visited Dad and my stepmother, Moe, in Florida for Christmas, he was easily tiring. Usually tight-lipped about medical matters, in March he took the extraordinary step of e-mailing me and my siblings that those health challenges had escalated.

Still, as I wrote about him, I didn’t comprehend the rate of Dad’s physical decline: by the time the column appeared in the June 2008 issue of Broward Family Life, he had passed away.

Though he never read the column, he heard every word.

That’s because a few weeks before he died, it hit me: I had a moral, ethical and personal obligation to share it with him before perfect strangers peered in on Dad’s life and our relationship.

This was no surface-level piece, but an intimate chronicling of my stumbling journey of figuring out how to be my father’s son. And when it came to exploring feelings, Dad was my polar opposite. When I dialed him up, I simply didn’t want him to be mortified when the column was published.

Reading it aloud, then, was one of my life’s most nerve-racking, heart-in-throat moments. What would Dad think? Would he be offended? Would he ask me (or order me) to remove anything that was too revealing or uncomfortable?

A few times, I got choked up as I read the Word document on my laptop. He didn’t interrupt. As I neared the end, the suspense soared alongside my heart rate.

“So,” I asked, “what do you think?”

“Wow,” Dad replied. “That’s really long!”

Such a quintessential Dad response: safe, factual, a tinge of mathematical. He had never been one to bare his soul, so why would this moment be any different? However, to his credit and to my great relief, neither did he ask that I alter a single word.

Along with my three siblings, I was at Dad’s side for his last days. That was such an enormous gift for all of us.

Every Father’s Day since, Dad’s generosity in blessing my column has been a bonus gift in my life. While he still had breath, that openness transformed my writing into a love letter; after his death, it has become a eulogy2.

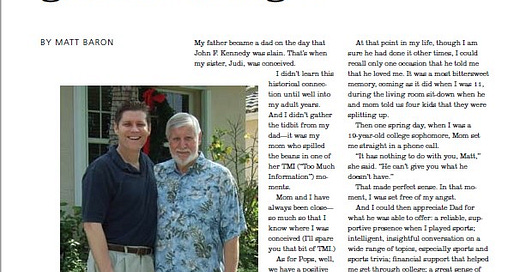

(Below is the first page of the column as it appeared in Broward Family Life. For ease of review, I have re-typed the entire column below the image.)

A Father’s Day tribute to a dad who gives all he’s got

My father became a dad on the day that John F. Kennedy was slain. That’s when my sister, Judi, was conceived.

I didn’t learn this historical connection until well into my adult years. And I didn’t gather the tidbit from my dad – it was mom who spilled the beans in one of her TMI (“Too Much Information”) moments.

Mom and I have always been close – so much so that I know where I was conceived (I’ll spare you that bit of TMI.)

As for Pops, well, we have a positive relationship that’s only improved over the years. But he’s someone I don’t really feel that I truly know.

This used to really bug me, peaking at something approaching anguish when I began college. It was the byproduct of my hyper-curiosity, a few introductory psychology classes and my more-than-nutritionally necessary alcohol consumption.

At that point in my life, though I am sure he had done it other times, I could recall only one occasion that he told me that he loved me. It was a most bittersweet memory, coming as it did when I was 11, during the living room sit-down when he and Mom told us four kids that they were splitting up.

Then one spring day, when I was a 19-year-old college sophomore, Mom set me straight in a phone call.

“It has nothing to do with you, Matt,” she said. “He can’t give you what he doesn’t have.”

That made perfect sense. In that moment, I was set free of my angst.

And I could then appreciate Dad for what he was able to offer: a reliable, supportive presence when I played sports; intelligent, insightful conversation on a wide range of topics, especially sports and sports trivia; financial support that helped me get through college; a great sense of humor; quirky habits like doling out ice cream after carefully divvying it up with a butcher knife; and unabashed hugs during our farewells.

As I reflect on this list, and as I have grown older and become a father myself, I am even more grateful for the negative, dysfunctional baggage that Dad has not given me.

We may not be bosom buddies, but Dad and I don’t suffer from any of the estrangement, resentment and other hurts that exist between all too many parents and children.

Meanwhile, our relationship has gradually gone beyond the surface.

A dozen years ago, I took the bold step, at the end of our phone calls, of telling Dad that I loved him. I could tell I caught him off-guard, but he replied in kind.

My siblings later told me that more frequently he was telling them he loved them, too. Now he even blurts it out to me before I say it.

Another indicator of our deepening relationship: my wife, Bridgett, can no longer detect when I’m talking to Dad.

For years, she would give a knowing chuckle when my chat with Dad would careen toward a familiar theme. Our dialogue would go something like this:

Me: “So we’re thinking about starting a family…”

Dad: “Oh, good. Hey, Red Sox have men on first and third, two outs. Here’s the pitch, Ramirez hits it up the middle, it’s through for a single!”

Me (sighing, resigned to this new topic): “Oh, great. What’s the score now?” (Bridgett suppresses a laugh in the background.)

Lately, however, our talks range more frequently beyond the Boston professional sports scene and into the meatier, more personal terrain of family, work, children, and the stuff of day-to-day life.

Since March, we’ve been talking a lot more about his health. He’s having trouble breathing, among other ailments, and in late April he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. I sent him a letter quoting Philippians, including an encouragement to “rejoice in the Lord always.”

I really don’t know if he’s going to go for that, frankly.3

But I’ve gotten to know Dad well enough that I also included some other material, such as alternative terms for congestive heart failure. One is FIFO (Fibrillation is Freaking Out) Syndrome, in honor of one of his favorite expressions. (He has always been a stickler with his first-in, first-out policy on consuming food.)

I have no idea how many more Father’s Days remain for Dad, but this much I do know: the Red Sox are playing the Cincinnati Reds on that particular Sunday this June and, more than ever before, I look forward to hearing Dad’s play-by-play account.

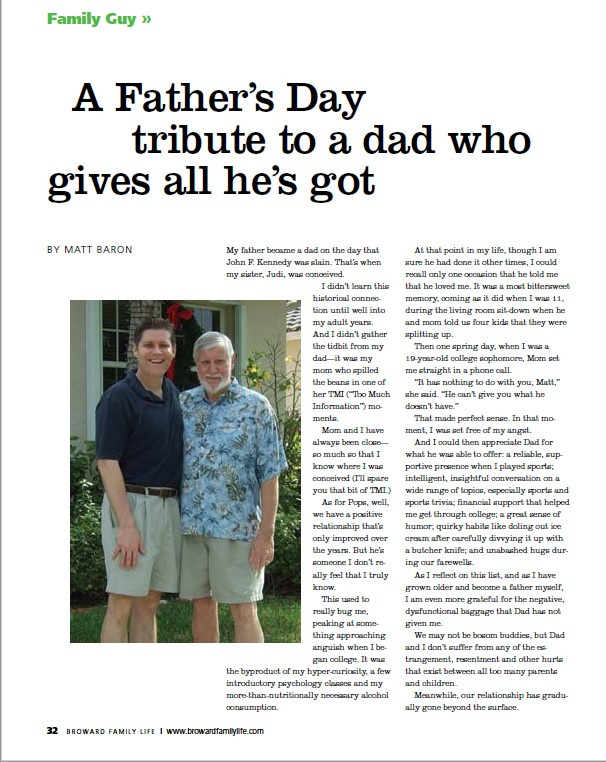

Matt Baron is the father of twin 4-year-olds, Zachary and Maggie Rose. For Christmas 2007, the family had a great visit with Grandpa Phil and Grandma Moe at their Port St. Lucie home.

At the risk of coming across as self-edifying, here’s Michelle’s longer answer:

“I found your original submissions…There were a total of four columns: Changing Kids Stories; Our Actions; Words Wield Power; and Then and Now. The piece that hooked me was Then and Now. I totally related to your story and loved every single word! …I began publishing Broward Family Life when my two daughters were in high school. When I read your stories, I was transported back in time and reminded of how judgmental I was when I first became a parent. The truth and humor of your words captivated me.”

Another note here that puts an exclamation point on the otherworldly timing that binds me with Michelle: she sold the magazine two months ago and yesterday she shut down her bank accounts and dissolved her corporation. “Matt, your timing couldn’t be better,” she wrote me Thursday. “Now that I am retiring, it’s wonderful knowing that my work made a small difference in someone’s world! I’m truly touched!”

If you’ve not yet done so, and even if your father is no longer alive, I encourage you to do the difficult, beautiful work of writing about him and your relationship with him. Too busy? Overwhelmed at the thought? Join the crowd. And ditto for writing something about your mother.

Turns out, he absolutely did “go for that” in his final days. Those last three days in hospice, Dad drew upon his Catholic upbringing, as well as our encouragement and regular reading of the Bible, to fully embrace the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The end was peaceful and poignant, with Dad surrounded by loved ones as a chaplain soothingly encouraged him to take Jesus’s hand. As if on cue, that’s when he drew his last breath.