Brother Love: `A Lot of Love Out Here’

Spending part of Easter near a highway on-ramp with my brother Phil

The frequency of my contact with my brother Phil varies wildly, so it only makes sense to mirror that in these writings.

Only four days ago, I shared about our April Fools, Night experience from a little over two years ago. It was my second chapter of Brother Love, coming a full month after the introduction of my complicated relationship with a sibling through his struggles with alcoholism, drug addiction and homelessness.

Today I share the third installment, an account of our time together on April 4, 2021, only three days later on that Easter evening.

If you’ve not yet done so, I recommend you read the previous chapter first, as it provides context for A Lot of Love Out Here. (That prior writing is linked immediately below.)

Brother Love: April Fools, Night

My eldest brother, Phil, has been homeless for much of his adult life. He moved to Chicago in February 2012, got a studio apartment a half-mile from my home and began doing carpentry projects — he’s got extensive skills and experience. However, within a year, amid heavy drinking and drug use, he slipped back into homelessness.

`A Lot of Love Out Here’

April 4, 2021 (Easter)

It’s 6:30 p.m. and I feel the need to get moving.

A few hours ago, Phil texted me with assorted, scattered details of the latest mishap/misadventure that had befallen him. That’s an apt phrase – it involved him falling, once again, on the railroad tracks a few nights earlier.

His final text: “BTW was at Rush hospital…helps a lot.”

I notice the messages two hours after they hit my phone. Pondering how to respond, it takes me a full minute to craft a text back: “Oh no. So sorry…now?”

He hasn’t replied in the hour that has passed, but I have a hunch about the answer to his current whereabouts. I get on my bicycle and ride along Lake Street, through the downtown with signs of commercial life starting to percolate after a year of COVID-induced dormancy and despair. Making my way to Harlem Avenue, I cross under the CTA’s Green Line and carefully traverse the sidewalk along the heavily trafficked thoroughfare.

Along the route, I spot a few panhandlers whose faces and mannerisms are as familiar as any neon sign or marketing slogan on this corridor. About 10 minutes and one mile into my trek, I spot Phil. His back is to me and he is conversing with a wiry woman I’ve seen plenty of times in this area. They are on the sidewalk’s edge where it gives way to the top of the highway ramp entrance to the Eisenhower Expressway.

She walks across the ramp entrance, presumably to resume her panhandling efforts with motorists exiting the highway eastbound.

My bike has come to a full stop, my feet firmly planted on the bumpy, weather-worn sidewalk that overlooks westbound Eisenhower traffic. Grinning, I contemplate my next move.

Wait till Phil turns and notices me? Jokingly holler something nasty to emulate the verbal abuse he’s told me about in his matter-of-fact, emotionally detached way?

But what if it’s not Phil?

I have been mistaken in the past when I think I’ve seen my brother out here plying his trade. Homeless men can bear striking similarities: the hunched posture, the layers of clothing, the slow shuffle along cars waiting out the red light.

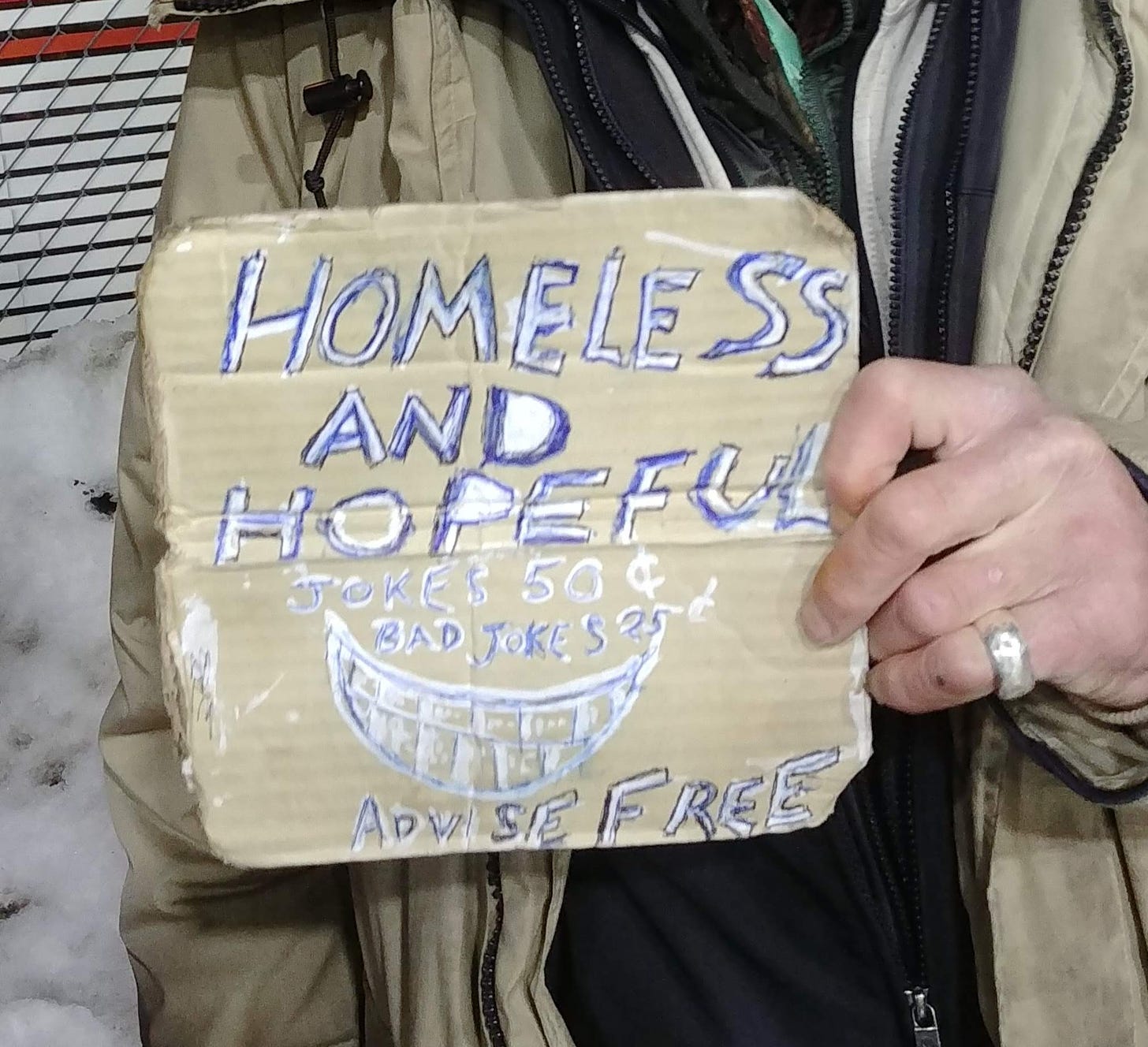

On this day, though, two strong clues serve as positive identification. The first is a makeshift stick-turned-cane in his right hand, which he is leaning on for support – a detail in synch with his earlier text about plummeting to the tracks. The second tell-tale indicator glitters when the sun bounces off it at just the right angle: a ring on Phil’s left pinky.

I chuckle at the memory of that ring’s discovery, and my role in it. A month or two ago, I had picked up Phil outside a Dunkin’ Donuts. As is often his way, Phil was eager to give me something. This time, it was a pair of thick winter gloves that he had obtained from a Good Samaritan. When I try them on, I feel something inside and pull it out: it’s the ring, which Phil joyously takes from me and slips on his pinky. “It fits!” he gushes.

That scene replays in my mind in the instant that the fellow panhandler ambles away. As for Phil, he remains oblivious to my presence. Several seconds pass, and I can’t stand my self-induced suspense any longer.

“Hello, brother!”

Phil’s reaction is a classic double-take. He turns towards me, looks away as if stunned, then looks back at me once more. Now the brace on his left leg comes into view as he limps in my direction. Neither one of us is masked for the first minute of conversation, then Phil follows my cue when I slip mine on.

It has been three days since I spent three hours of a frigid evening with him, and he fills in the blanks of that interim. More play-by-play of detail to flesh out the skeleton of his texts. He has just gotten here to this spot and is about to start panhandling, he explains. He’s got 35 dollars in his pocket, which he demonstrates by peeling out a wad lined with one-dollar bills.

“I know there’s a 20 in here, too.”

“That’s OK,” I reply. “I’ll take your word for it.”

“What do I owe you?”

“Nothing,” I say. “You don’t owe me a thing, Phil.”

Early this morning, he had left me three straight voice mails. On one, he asked when my church’s Easter service was happening. We exchanged texts and, thinking he might come, I kept an eye out for him. He’s come to services before, when we met at Michele Clark High School, and three nights ago I had brought him to the outside of the new building we moved into.

Still, cars whizzing by us as we chat, he says: “I forget where your church is.” I remind him of the location, then take the opportunity to reiterate that he’s welcome there any time, and that he’s loved, that there’s no judgement.

Now that we’re on this topic, I take the opening to share some of Pastor Jon’s sermon points from today. One in particular had brought Phil to mind as Jon shared it: when something goes wrong in our life, that’s not God punishing us. He poured out His wrath on Jesus at Calvary. Jesus took our place for our sin, so that when God sees us – even in our mess-ups – He sees the righteousness of Jesus that covers us.

“Matthew,” Phil says, peering over his glasses and deeply into my eyes.

His blue eyes are those of our own earthly father, the one who embraced Jesus on his hospice bed 13 years ago. Phil was often in the room, but he had mostly kept a distance as Andy or Judi or I read scriptures that Dad suddenly, dramatically couldn’t get enough of in those final few days.

“Matthew,” Phil says, leaning in toward me. “I have no shame.”

“That’s great,” I reply, unsure if he’s intending a double meaning with this remark, or if he’s genuinely not feeling shame.

One thing that is for certain: Phil is concerned for my safety. With cars passing by at close range, he motions for us to go away from the ramp entrance, down the incline about 75 feet and dipping into a space set back several feet from the street.

Joining us briefly is Phil’s friend “Gambit,” with flowing white hair and salt-and-pepper beard. About six weeks ago, according to Phil, Gambit was struck by a car and wound up at Loyola University Medical Center a few miles away.

He was discharged only a day or so later, and he’s been back at it with Phil and their fellow panhandlers in the median of Harlem Avenue. At one point, Phil points out that Gambit is “doing the statue,” a state in which heroin users essentially freeze up and resemble a statue.

Looking at Gambit, I see a guy who appears to be leaning down to get something in or out of a duffel bag as traffic stacks up near him – but Phil sees it differently. Maybe it’s a metaphor for us two: we often see things differently. On this day, I’ve been drinking lots of water (as is my custom), while Phil is supremely loaded (as is his). He’s been having a steady stream of vodka mixed with soda. Could be that my sobriety is no match for his street-smart perception and fellow panhandler analysis.

Gambit descends a trail, toward the highway, and appears to be ingesting a substance of some sort. My guess is that it’s heroin, which has been Phil’s major addiction the past few years (though he’s not been doing it much lately, he reports).

I consider asking Phil what Gambit is doing but then come to this in my mind: I really don’t care that much. I care about the person, especially since he and Phil are chummy and look out for one another. But in this moment, the subject of what particular drug he may be using – it’s just so utterly boring.

Phil says that Gambit has been married and has a couple of kids; he also remarks that his own “saving grace” is that he has never had kids. The sense I have, from a variety of Phil’s comments along this vein over time, is that Phil would be wracked with guilt if he had children. Then again, I wonder if he’d have made different decisions along the way if he had a child or children in his life.

It's nearly 7:15 p.m., getting close to dusk. Time for me to start biking home. I ask Phil if I can shoot a video of him to share with our siblings. He agrees, but says he first needs to compose himself. A few moments later, I begin recording the 12-second clip.

“A lot of love out here,” he begins, his body slightly swaying. “A lot of love everywhere.” His right eye squints and Phil gives a slight nod toward me: “That’s my Brother Love.” A smile flickers briefly across his face.

“Happy Easter, brother,” I reply, chuckling. “I love you.”

“Happy Easter.”1

My goal in sharing these and future Brother Love stories: for as much good as possible to flow from the struggles that Phil has endured and, to a much lesser degree, that I have experienced throughout this journey. May each one offer encouragement to those in similar circumstances and insight to everyone else.

Please say hi for me and get a phone number if he has one.

Love ya cuz.