Brother Love: `Get the F*&% Out!’

On Wednesday evening, a visit with my brother Phil begins as a stakeout and ends two hours later as he delivers a gruff F-bomb goodbye. We have different ways of expressing our love for one another.

It’s a pleasant Wednesday evening in Chicago and I’m on a stakeout, reflecting on some of my previous wait-’em-out excursions.

Most have come in my work as a newspaper or magazine reporter, such as the time in May 2002 when I tried to prevail on the roommates of Smiley Faced Bomber suspect Luke Helder to speak with me at their off-campus apartment in Menomonie, Wisconsin. Five years later, during the height of media frenzy over the disappearance of Drew Peterson’s fourth wife, Stacy, I knocked on the cop’s front door in Bolingbrook, Illinois

There have been too many other ones to remember, enough that I know I’ve got the endurance to see this one through. My focus this time is my brother Phil, whom I haven’t seen in over three weeks.

By the time we conclude our two hours together, I’m grateful to have caught up. But as with most every interaction I’ve had with him over his 12 tumultuous years in Chicago—a period of chronic drug addiction and alcoholism, mental health struggles and frequent homelessness—it also takes an emotional toll.

Although I don’t know quite how I feel about my encounters with Phil, I feel a duty to persevere for as long as he’s able to draw breath. To show up, to remain available…in for an inch, in for a mile.

This evening begins with the 10 miles I drive from my home to Phil’s apartment building in Chicago’s South Loop. When my knocks on his door go unanswered, I scrawl a brief note on a box of Nutty Buddy bars, then slip the Little Debbie staple beneath Phil’s doormat.

I retrieve my driver’s license from the security guard at the front desk—my ticket for entry—and tell her that I’ll wait in front of the building. Ten minutes later, I look up and here’s Phil ambling along the sidewalk. Laden with groceries, he barely acknowledges my enthusiastic greeting and declines my offer to help carry a few bags.

To the guard inside, he says simply, “You know this guy.” Phil’s conspicuously not referring to me as his brother, though she’s held my ID at least 15 times over the past year.

Phil is in head-down, don’t-talk-to-anybody mode and it’s my duty to match it. Once in the elevator away from any prying eyes and ears, Phil grumps, “Don’t f*&% with me. Got a lot of shit going on.”

I keep my mouth shut. Phil’s having a bad day, maybe a bad week, quite possibly a bad 23-day stretch since we last hung out at his studio apartment. One of the consequences of his not having a phone since September is that I have no clue about his ups and downs until the next time I see him.

Within two minutes, I know to tread lightly. Getting off the elevator, I follow quietly in Phil’s wake as he verbally stiff-arms his next-door neighbor’s friendly “how are you doing?”

“Average,” Phil barks.

At his door, he reaches down for the Nutty Buddy box and reads my note. Once inside, Phil directs me to sit in a chair while he unloads his groceries. It’s about 10 minutes before we embrace, a robust five-second squeeze—likely his first extended human contact since my last visit.

Turns out he’s been sick a lot lately. He says it’s because he’s trying to wean himself off his fentanyl/heroin mix; he’s also drinking less of his vodka-and-soda concoction. Though still panhandling, Phil says he recognizes the futility of it all—all the danger and tedium that’s baked into the process. Standing on the corner of a busy intersection, making his drug purchases in sketchy areas of the city, all his time-consuming bus and train rides.

I affirm his efforts but don’t ask about the possibility of checking into a rehabilitation program—he’s been to more than his share and has mixed emotions about them, at best. Besides, Phil wants to show me this cartoon strip he’s made on a poster board that he plucked from an alley garbage can.

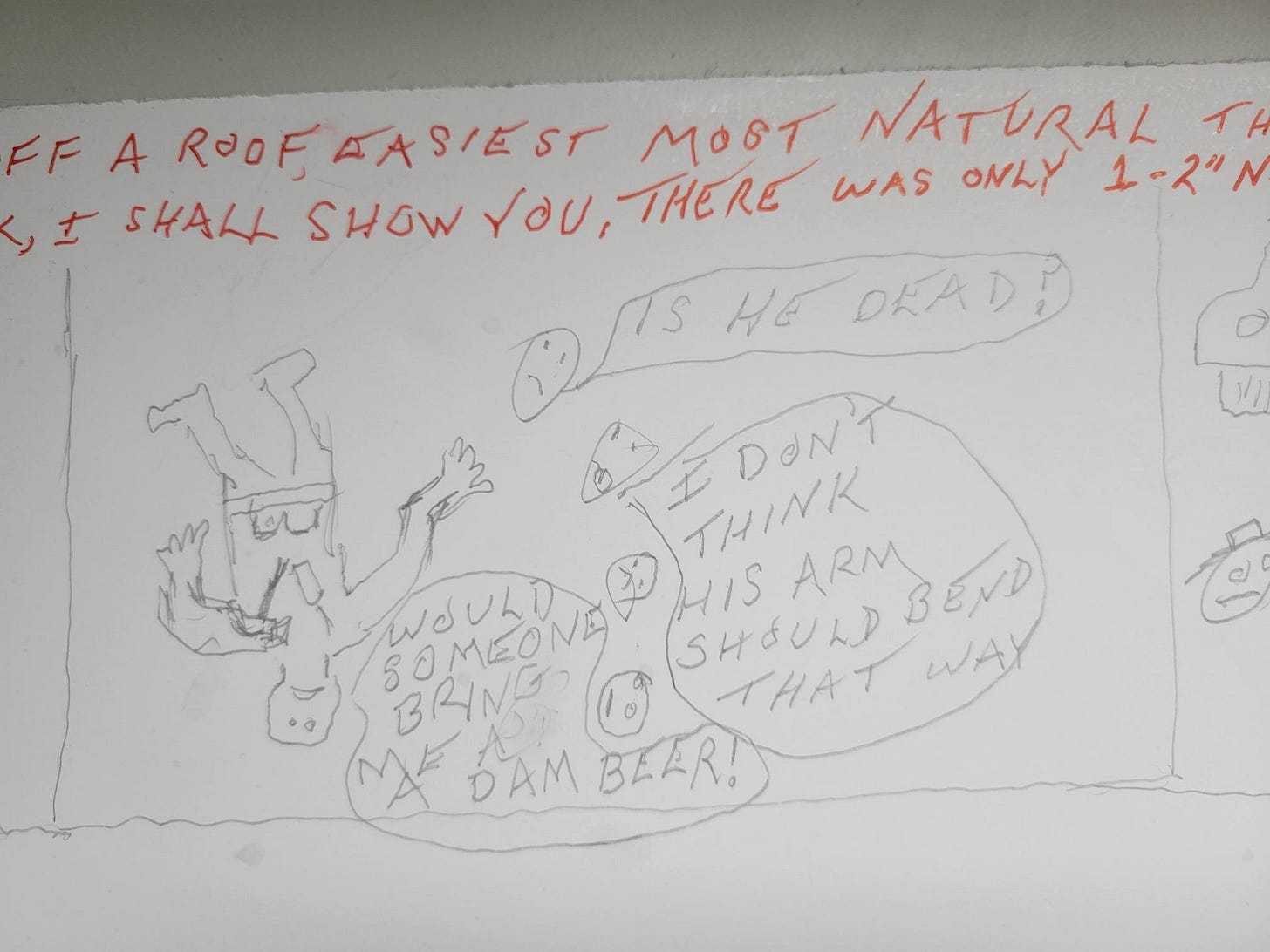

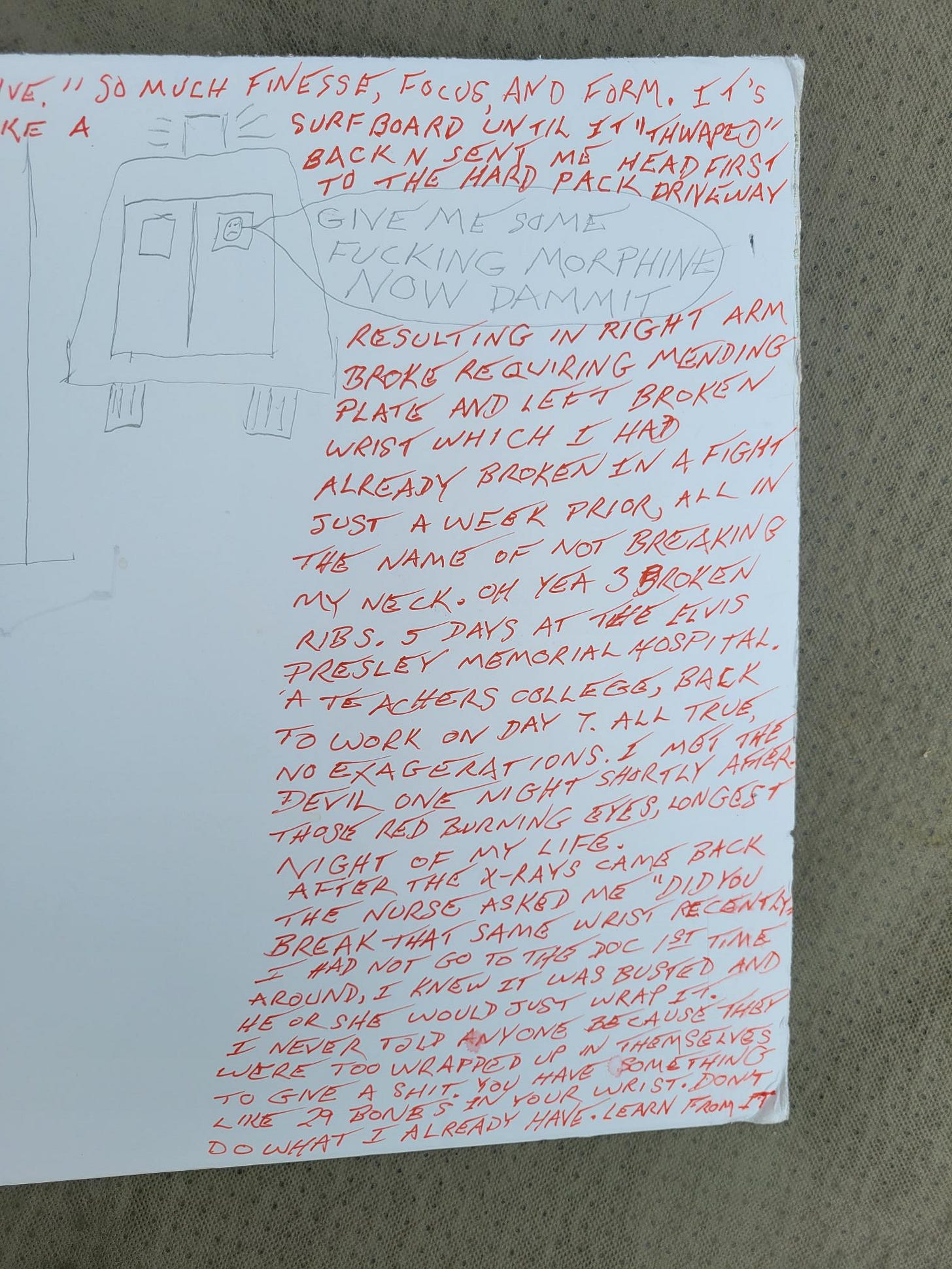

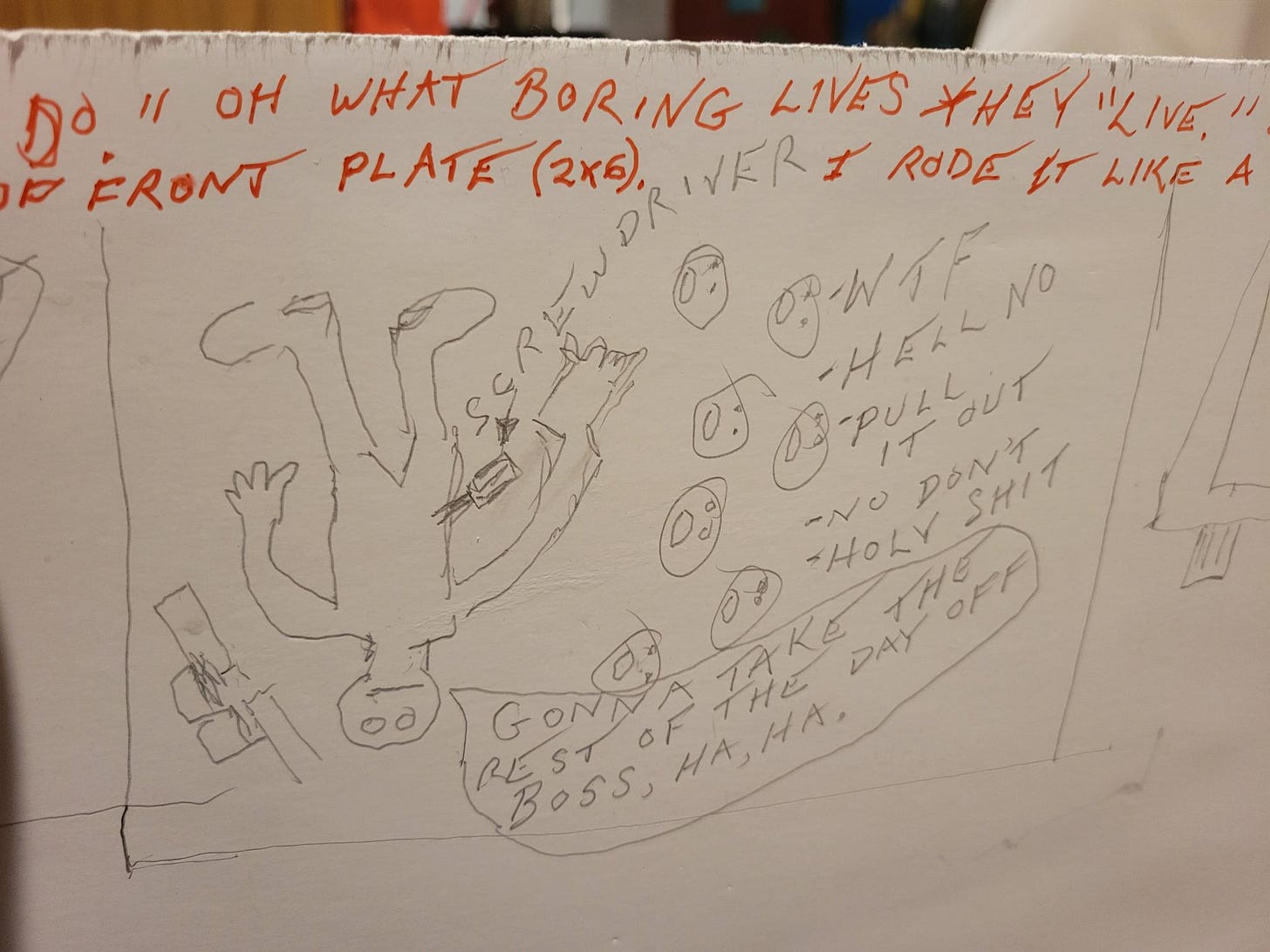

On one side is what appears to be a high school student’s overview of their family tree; on the other side is Phil’s recounting of the time he tumbled off the roof of a Marion, Arkansas “hillbilly grocery store” that he was working on, circa 2010.

In addition to the cartoon panels is this narrative:

Most people will tell you, `Falling off a roof, easiest most natural thing a person could do.’ Oh what boring lives they `live.’ So much finesse, focus and form. It’s all about sticking the landing. Enough talk, I shall show you. There was only a 1-2” nail holding the last 4” of front plate (2 x 6). I rode it like a surfboard until it `thwaped’ back n sent me headfirst to the hard pack driveway resulting in right arm broke requiring mending plate and left broken wrist which I had already broken in a fight just a week prior, all in the name of not breaking my neck. Oh yea, 3 broken ribs. 5 days at the Elvis Presley Memorial Hospital…”

I ask if I can share this here and, as he’s done with everything else I’ve posted on this Substack the past year, he gives his approval.

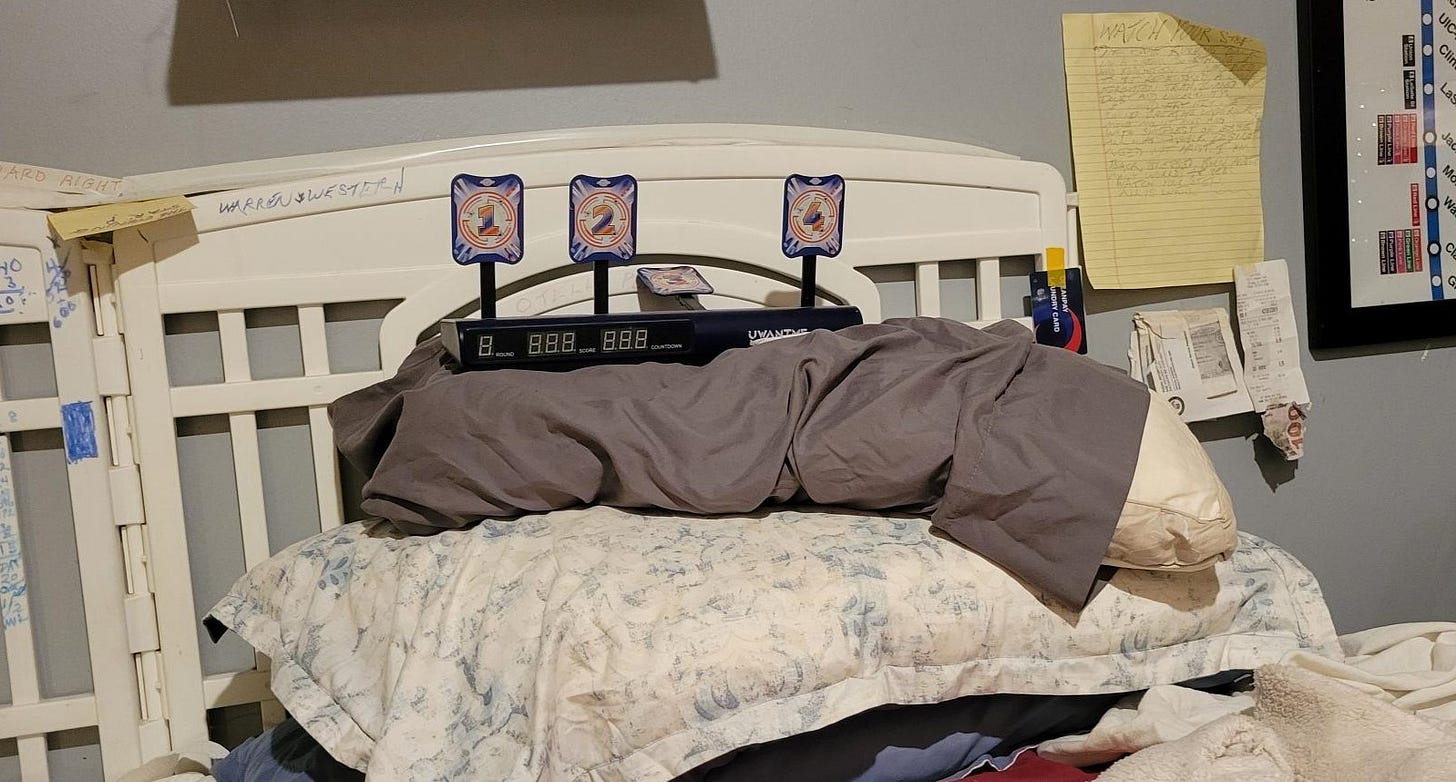

Later, Phil invites me to play an improvised game—let’s call it Blowpipe.

It consists of blowing a thin strip of wadded-up construction paper from a pipe. The goal is to knock down carnival-style levers propped up on a pillow. It strikes me as an homage to Phil’s years working in a carnival—that’s what he did, among other things, for the several years he lived in Arkansas.

I’m game to try Blowpipe. The clincher is when Phil emphasizes we’ll use opposite ends of the pipe. He racks up five points by knocking down a “2” and a “3.” I knock down “3” twice, though I had the benefit of extra turns that Phil insists on.

It’s not really a competition so much as an amusing diversion. Afterwards, Phil feeds me ice cream; I catch him up on family.

Throughout, alternately in the background and foreground is Breaking Dawn, Part I, one of The Twilight Saga movies. There’s lots of blood spurting everywhere and young, attractive people turning into animals, then back into people, at which point they are arrayed as if poised for a clothing catalogue photo shoot that's about to break out.

The fantasy flick is disorienting and altogether a perfect complement to our erratic evening.

When it mercifully ends, I decline Phil’s invitation to see the sequel—he has the whole series, as part of his vast collection of DVDs—and say I’ve got to get going. But my departure is delayed when he cannot open the door: Between the bags he was carrying and his brother surprising him, Phil had forgotten to remove the key from the lock when we arrived and I'd quickly turned the bolt.

I return to my seat, confident in my handyman brother’s ability to pry the key out of the lock. Five minutes later, he’s got the door open.

As I get moving, I suggest a parting embrace. Instead, with the door cracked open halfway, he urges me to step into the sixth-floor hallway.

“Get the f*&% out!” he says, employing his gruffest tone. “Don’t talk to anyone…get the f*&% out!”

By “anyone,” he means anyone in his building, a place where he senses people are plotting against him. He’s mentioned this a few times tonight, without elaboration. I don’t press for details. Mostly, I think he’s being paranoid—and I know that any conversation I engage in will reveal my skepticism and draw more of Phil’s ire.

So, I’ve left it alone. Similarly, Phil wants these miscreants (imagined or real) to leave me alone. He says they are capable of following me home and preying on me and my family. I wonder, but only to myself, how much he’s influenced by the violence of Breaking Dawn.

Ultimately, I recognize this unorthodox, unfriendly farewell as a coarse covering atop a protective, loving shell. He’s trying to snap me to attention, to get me to be on guard. It’s what he knows. It’s how he’s survived through all those years of homelessness in every continental U.S. time zone. No doubt he feels it’s helped him navigate thousands of interactions with dangerous people engaged in criminal activity.

Intellectually, I can see it from his perspective. He loves me and wants me safe, therefore I should “get the f*&% out!”

Still, it would’ve been nice to share a goodbye hug.

*********************************

In addition to being a free or paid subscriber to The Inside Edge, you also have the option to support my writing for any amount you choose via Venmo.

I appreciate the comments that people leave on my columns, including e-mail replies from subscribers. Please keep them coming! Also, if you are open to posting comments on my Substack page, I’d appreciate that, too.