Fidrych? Get out of here!

How my brother Andy’s midday stroll snagged a famous baseball Bird

“Get out of here.”

More than a few times, those words — with salty modifiers interspersed — were one of my newspaper editor’s favorite refrains throughout the 1990s. Back then, the newspaper office in Elgin, some 40 miles northwest of Chicago, was where my colleagues and I wrote virtually all of our stories.

But to tell fresh stories that none of our competitors had, the key was to go out and find them — they were not going to simply fall into our lap.

On this day exactly 25 year ago, for example, I was the only reporter in the newsroom one Sunday. Mixed in with other reporting — mostly police news — I kept tabs on the Chicago Bulls as they tried to close out the Utah Jazz in Game 6 of the NBA Finals.

Then, as the fourth quarter began, I shifted from fan to reporter and got out the door to a nearby bar. There, I began capturing what I hoped would be the team’s sixth championship in eight years. Here’s how it panned out:

This “get out” directive wasn’t unique to our newsroom, of course. While I was plying my journalism trade here in the Chicago area, my brother Andy was pursuing a parallel career 1,000 miles to the east near Boston.

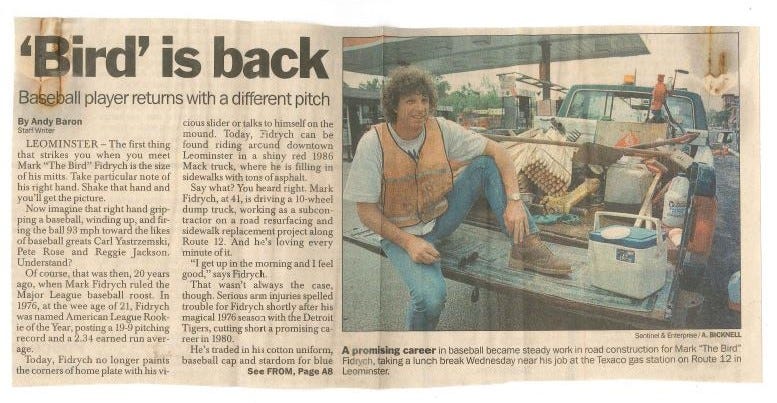

During his six years at the Sentinel & Enterprise of Fitchburg, his midday routine was to get out of the newspaper’s Leominster office and wander around, see what he might come across. One spring day, that practice, coupled with friendly gumption, paid off big-time. Strolling along the sidewalk near a red light, he saw a red Mack truck, emblazoned with “The Bird” on its door and bearing a logo of a bird winding up to throw a baseball.

Andy knew that Mark Fidrych, the former Major League Baseball phenom, was a subcontractor and lived about 20 miles away. So as he strode toward the truck, idling at the light, he thought he knew what he’d see when he crouched down to get a closer look.

“I saw that mop of hair and I said, `Fidrych?’” Andy told me last week.

Fidrych: “Yeah.”

Andy: “Wow, I’d really like to talk to you.”

(By this point, the light has turned green.)

Fidrych: “Well, if you want to talk, you’ve got to get in.”

We interrupt this vignette with some context for those who might need it:

Fidrych was one of the most charismatic, lovable, off-beat, down-to-earth characters in Major League Baseball history. On top of that, he was an excellent pitcher, if only for a short while before injuries derailed his career. He blazed onto the national pastime stage in 1976, just as Andy and I were embarking on our lifelong love affair with the sport.

In fact, the first big-league game we attended, at Fenway Park in Boston, came three days before Fidrych’s first start as an eccentric 21-year-old kid for the Detroit Tigers.

He won nine of his first 10 decisions, including a Monday Night Baseball game against the New York Yankees that brought him to another level of national prominence:

Two weeks later, he was the American League’s starting pitcher in the All-Star Game.

By season’s end, Fidrych had won 19 games for a pretty lousy Tigers squad, was the runaway Rookie of the Year in the American League and placed second for the honor bestowed on the league’s best pitcher, the Cy Young Award. (He received one Most Valuable Player vote, though modern metrics suggest he should have received even more consideration: his 9.6 Wins Above Replacement (WAR) rating easily surpassed everyone else in the AL and tied National League MVP Joe Morgan’s WAR.)

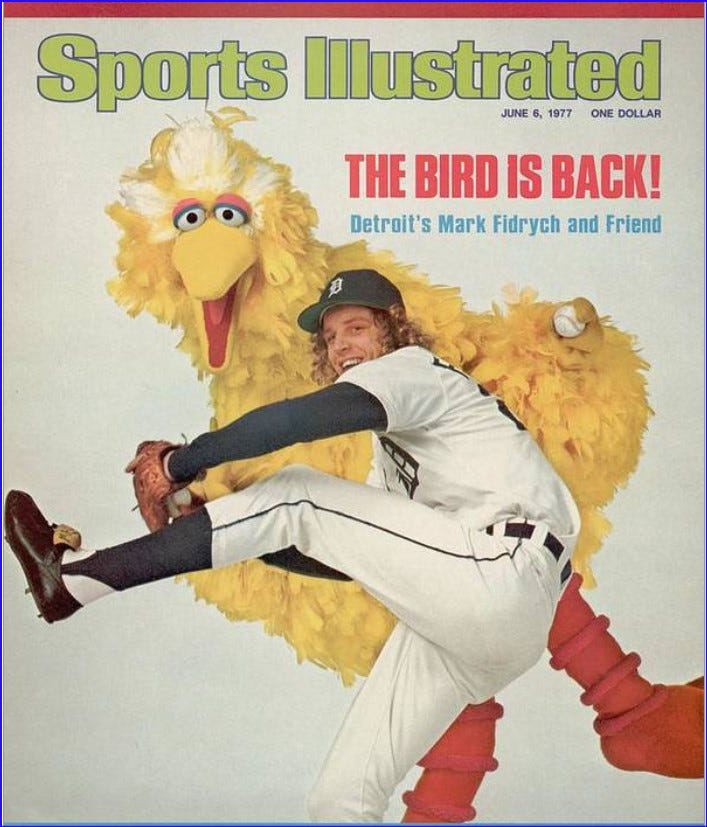

Early the next season, Fidrych appeared on the covers of Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated. It was part of the fanfare that catapulted him, complete with a genuine aw-shucks persona, to folk hero status.

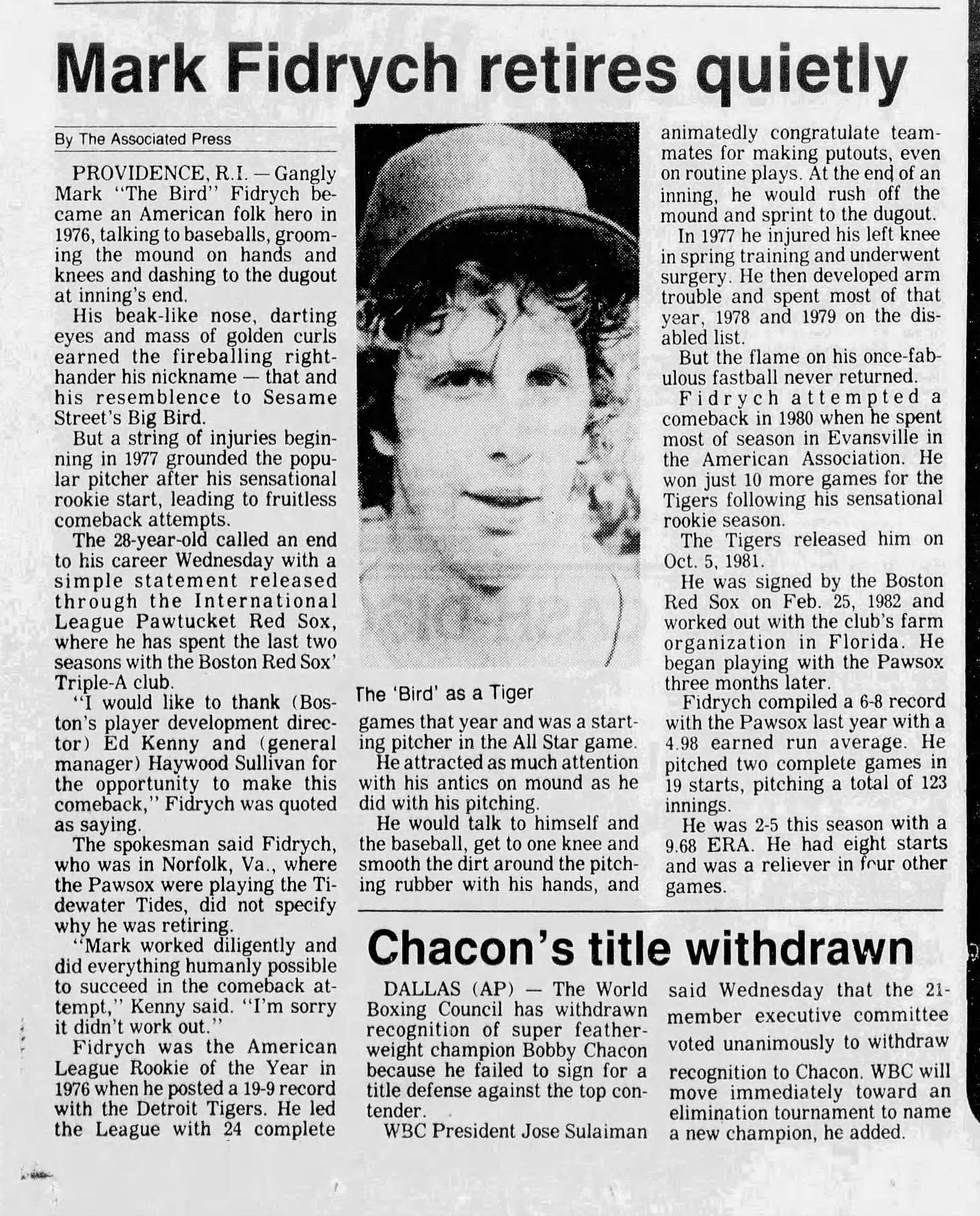

Alas, four injury-riddled seasons followed; at 26, Fidrych pitched his last game in the Majors. Three minor-league seasons later, he retired, falling short in his quest to come back with his hometown Boston Red Sox. “Quietly” is how this headline described the moment:

So, this is the guy who pulled up to that red light close to where Andy was looking for…well, what was he doing anyway?

“I would just look for stuff…I didn’t know what I was looking for,” Andy explains. “When you’re a reporter, it gives you license and a certain amount of courage to do things you wouldn’t normally do.”

Like, strike up a conversation with a stranger at a red light. Only, Fidrych was hardly a stranger to so many fans, including Andy. The moment could have ended there if Fidrych simply chose to shrug off this young guy approaching him — or even offered a friendly wave.

But that wasn’t Fidrych’s character.1

At Fidrych’s impromptu invitation, Andy jumped in. Over the next hour or so, he went from a routine amble to the most spur-of-the-moment article of his journalism career. He tagged along as Fidrych – open, affable and witty – delivered gravel to a nearby house. He talked about the past with gratitude, though it also struck Andy that Fidrych “was unfazed about being in the Major Leagues.”

“He had a confidence about him, even in 1996. My sense was he knew he belonged (in the Majors), even though everyone in the baseball world was probably like, `Who the hell is this guy?’” Andy recalls. “He had a real friendly demeanor; he had a breezy way about him, very good natured.”

After Fidrych dropped my brother off at his newspaper office, a staff photographer came out to snap photos of the folk hero outside the gas station roughly where his path crossed Andy’s. The next day, this story appeared on the front page:

It was a terrific piece of enterprise reporting, on top of being a memorable personal experience. But for the past 27 years, Andy has had a nagging feeling that something was missing.

“When I wrote it, I didn’t give any backstory about how it came about, which is an even better story,” Andy mused. “A reader might have been, like, `How the hell did you find this guy?’ In retrospect, maybe I should have done a sidebar.”

Consider it done, Andy.

As much as Fidrych was admired for his joyful, child-like pitching prowess, he was beloved even more for his kindness and lack of bitterness over the decline of his playing career. One evidence of those qualities: his guest-starring role in Dear Mr. Fidrych, a low-budget movie written and directed by Mike Cramer that I had the pleasure to see. Tragically, Fidrych, only 54 years old, died in a 2009 accident shortly after the film was shot.

Great story, loved watching Fidrych his rookie year. Especially when he would talk to the baseball.

Fantastic story!