`Let's be careful out there.'

After George Santos's House expulsion--and in the midst of my binge-reading and listening on other charlatans--we must not grow numb to our role in detecting, and calling out, scammers of all stripes.

Over the past month, I’ve read four books:

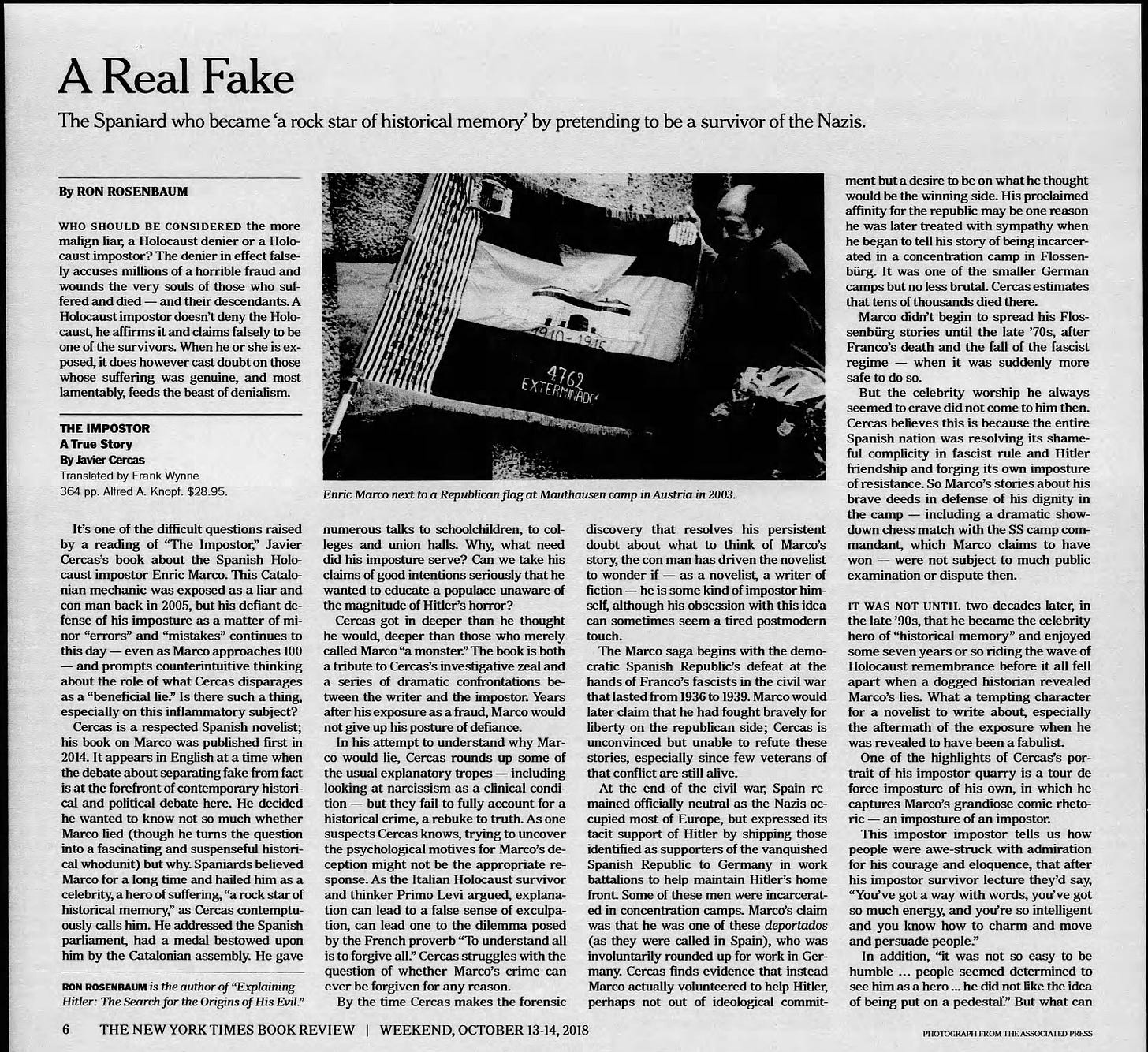

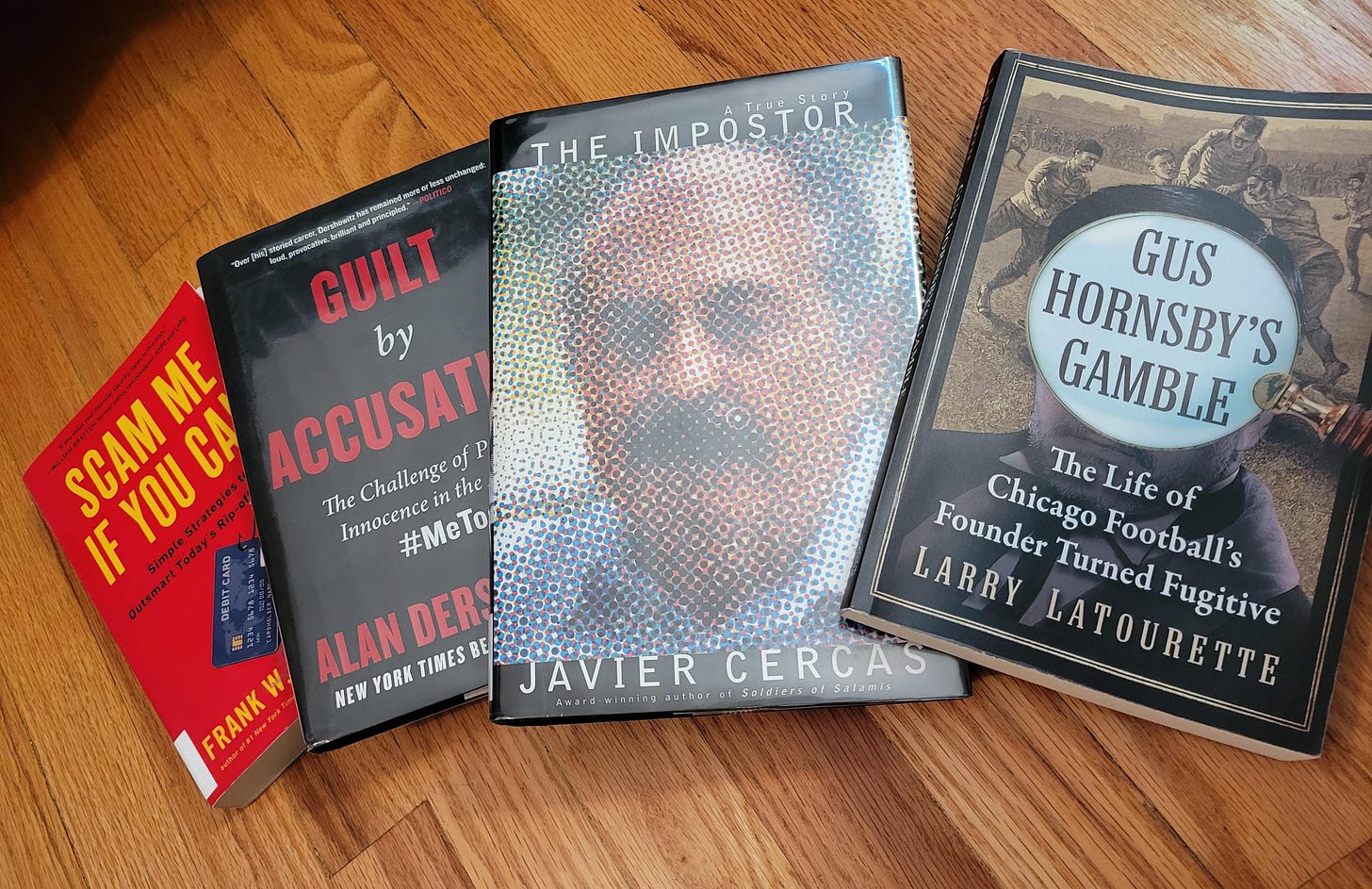

The Impostor, by Javier Cercas, about a Spanish man named Enric Marco who claimed to be a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, a crusader for justice, and a Holocaust survivor. He was exposed as a fraud in 2005.

Scam Me if You Can: Simple Strategies to Outsmart Today’s Rip-off Artists, by Frank W. Abagnale. (He also wrote Catch Me if You Can, which was made into the 2002 movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio.)

In this book, Abagnale lays out defenses to some of scammers’ most scurrilous tactics, including identity theft, real estate ruses and nefarious charity come-ons.

Guilt by Accusation: The Challenge of Proving Innocence in the Age of #MeToo, by Alan Dershowitz. In this 2019 book, the retired Harvard law professor and media/cultural lightning rod lays out the arduous journey he took to refute an allegation of sexual misconduct by Virginia Roberts Giuffre.

Giuffre never took Dershowitz up on his challenge to make her accusation outside of a court filing that shielded her from criminal liability. In 2022, she acknowledged that she “may have made a mistake” in accusing him.

Gus Hornsby’s Gamble: The Life of Chicago Football’s Founder Turned Fugitive, by Larry LaTourette.1 Set mostly in the late 1800s, this meticulously chronicled account has Gus Hornsby at its center.

As the “fugitive” reference in the title foreshadows, Hornsby briefly is on the run from the law before a prison term for financial fraud marks a low point in a fascinating 83-year life.

I also just finished listening to a terrific seven-part podcast series hosted by Justin Sayles and produced by The Ringer called “The Wedding Scammer.” The focus: an identity-changing scammer (original name: Carl Butcho) who employs a variety of aliases as he hoodwinks people (including Sayles) across industries and in several states.

Notice a theme permeating these works?

Why do you suppose I am so consumed with this topic?

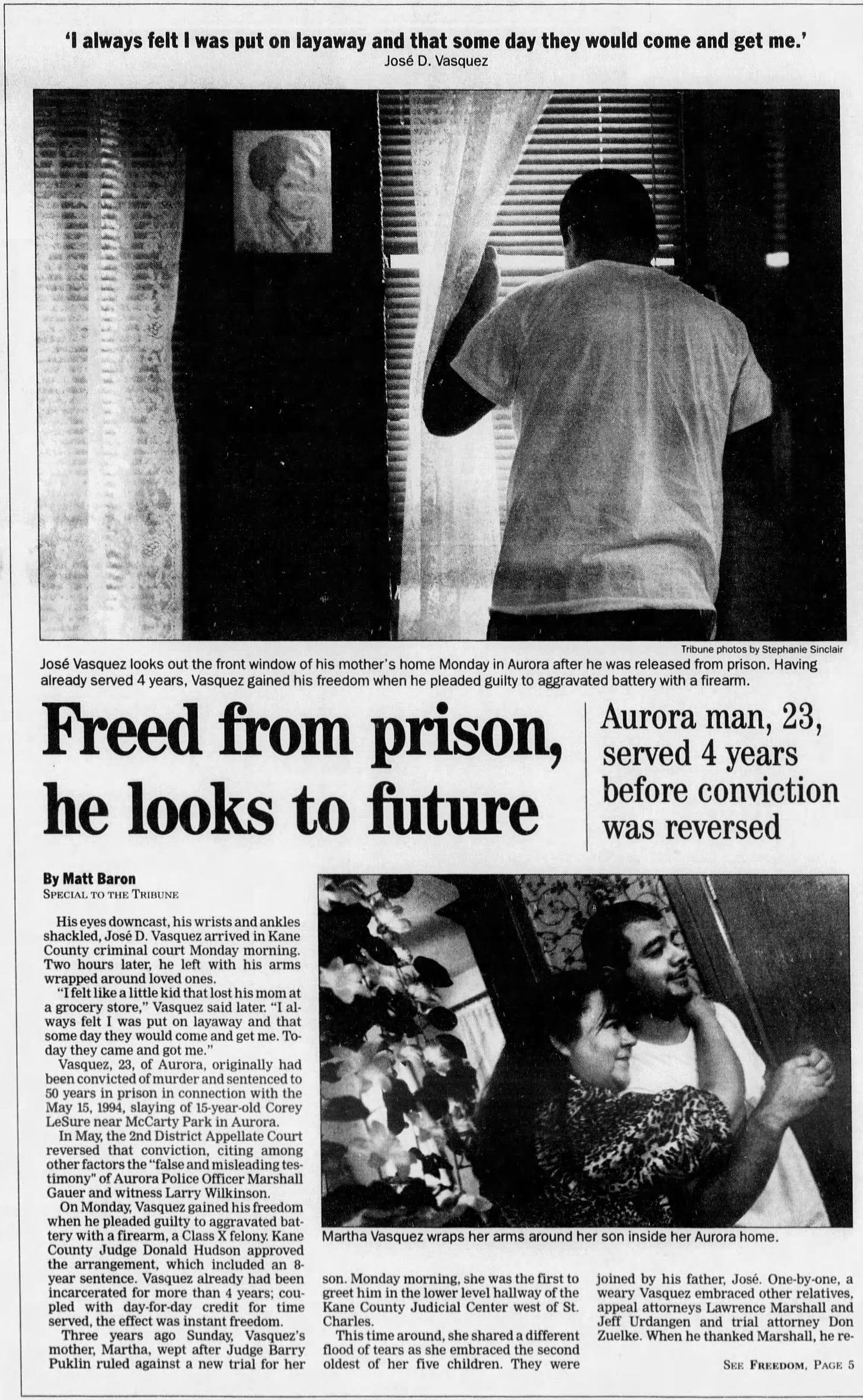

Partly, I know it’s because that I have enjoyed those occasions when I am able to help expose such scoundrels. Most often, that’s been through my work as a newspaper reporter, with the most satisfying example coming in 2000.

The saga involved a police detective whose deception played a key role in convicting a young man for murder…

…only to have that deception come to light, and the man, Jose Vasquez, freed from prison.

But my heightened focus on this subject goes beyond my usual level of passion for justice. I am gripped by the uneasy sense that, as a culture, we are growing numb to scammers. With what feels like so many of them in our midst, from texters and e-mailers and robo-callers to those in positions of power and influence, that numbness can be a kind of coping mechanism.

Rather than face the painful reality of yet another scammer, we bury it. With indifference. With exasperation. With distraction. With whataboutism:2 “Come on, he/she/they are not nearly as bad as that one over there!”

For every George Santos, exposed as a scammer and expelled yesterday from the House of Representatives, there are innumerable unknown con artists lurking about. One of the sad byproducts of this environment is that it raises our guard against those who are authentically, honestly, ethically seeking connection of some kind.

As a result, there is an erosion of trust in our fellow citizens, as this Pew Research Center study revealed:

Just as Jussie Smollett has undermined legitimate victims of hate crimes…

Just as Dershowitz’s false accuser has undermined actual victims of sexual misconduct—and even instances where she herself was the victim of sexual misconduct…

Just as unfounded claims of election fraud in the 2020 U.S. Presidential election lay the groundwork for potentially legitimate claims of election fraud in the future…

Wearisome and discouraging as it all can be, we must still be vigilant in spotting, then calling out lies—and insisting on real consequences—when we detect them. The expulsion of Santos is a positive step.

As Axios reported yesterday in the aftermath of Santos’s expulsion, “The last straw for many lawmakers was the Ethics Committee report, which detailed `substantial evidence’ of `uncharged and unlawful conduct’ including allegedly stealing from his 2022 campaign.”

I suppose that on some level, I’ve gone on this reading and podcast-listening binge to gird myself for the 2024 U.S. Presidential campaign season to really heat up. On top of the scam-saturated perils of our everyday lives, we are in for a doozy of a stretch run toward the polls on November 5th.

How can we end on a more hopeful note? At this point in my reflections, for some reason, what came to my mind was the late Michael Conrad, the actor whose most notable role was Sgt. Phil Esterhaus in the 1980s drama Hill Street Blues.

As a youngster glued to the tube on plenty of those nights, I found it reassuring that he’d wrap up roll call each time with the same message. Whether you’ve seen it scores of times before, or don’t have a clue what I’m referencing, I invite you to invest less than 10 seconds by clicking on the clip below.

Larry is a friend, dating back to college.

Whataboutism is “the technique or practice of responding to an accusation or difficult question by making a counteraccusation or raising a different issue.”

I'm surprised that you would trust anything Abagnale writes. https://whyy.org/segments/the-greatest-hoax-on-earth/

This deserves more than the quick read over I gave it, and study by subject-area experts, not me, but my first thought is that it belongs on your "best of" "Inside Edge Substack" page.

About Whatboutisms. My general thought is that we should absolutely never forgive our own sins because others are guilty of the same, or of things that are more or less the same. However, I don't appreciate being called out on my sins, or at least having my mistakes characterized as sins. If I feel the person leveling the accusation is guilty of hypocrisy, I am not above offering a Whataboutism.

I do find a mustering of a Whatboutism when discussing the flaws of other people or institutions among uninterested observers to be weak and aggravating, for the most part. When one's interlocutor does that, the conversation generally doesn't go anywhere. It just trails off, and nothing is solved. Maybe the reason is there are an endless supply of possible Whataboutisms? I suppose it can be a good exercise, though, to think about whether things really are or are not equivalent. And note that the term Whataboutism suggests a question of equivalency, not an assertion of equivalency.