Powerball Party

25 Years Ago, a Fairy Tale Start to a Story That Turned Sour

Just about everyone’s a self-proclaimed expert on money, and how it should be used.

This is exponentially true when it’s somebody else’s dough, as I observed in a 2021 essay about then-Chicago Tribune columnist Rex Huppke’s two cents on how multi-billionaires Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos should spend their money.

And when someone wins the lottery? All bets are off — everyone surely has something to say about what they would do if they found themselves in enormously good graces with Lady Luck.

A quarter-century ago this week, that was one of the subplots of a story involving a pair of Streamwood, Illinois bartenders and Frank Capaci, a bar regular for whom they had driven to Wisconsin to purchase the then-record-setting Powerball ticket worth an estimated $195 million1.

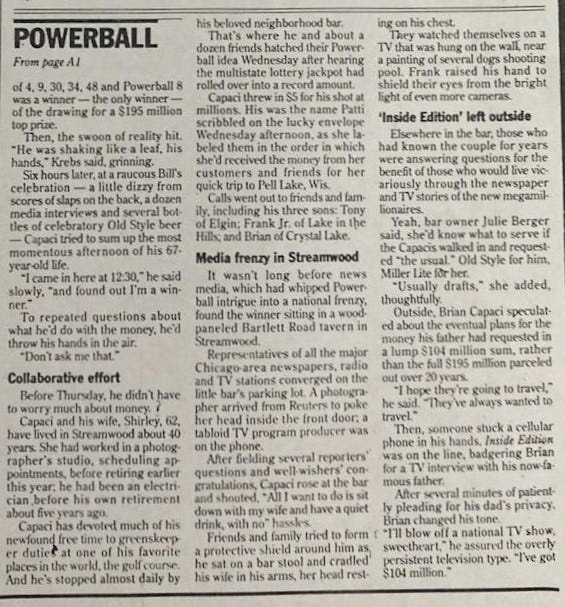

On assignment for my Elgin, Ill.-based daily newspaper, The Courier News, I met them all on the evening of May 21, 1998. By the time my colleague, Sean Noble, and I got to the bar at the heart of it all, Capaci, a 66-year-old retired electrician2, had been buying rounds of drinks for everyone. He was well into the `media darling’ phase of his 15 minutes of fame.

A turbo-charged revelry permeated Bill's on Bartlett Pizza Pub in celebration of the mind-blowing, out-of-this-world news. A vignette from a year-end story that I wrote seven months later recapping the surreal night:

At one point, Capaci stood up, shushed everyone in the bar and announced: “I don’t care if I am a winner. All you people…people that know who I am…we are friends. This will never disintegrate. And as long as I’m alive, we’re gonna drink free!”

The day after his win, I wrote a feature pondering the possibilities that suddenly existed for Capaci. They included a variety of outlandish notions, like buying enough cases of his favorite beverage, Old Style, to lay them end-to-end from his Streamwood watering hole to Miami.

It felt like the first chapter of a fairy tale. Cinderella, Snow White…and Frank John Capaci Sr.

There were two core ingredients in the story’s appeal:

Capaci’s blue-collar work ethic.

The morning after his triumphant revelry, he showed up for his 5 a.m. shift at the golf course where he worked as a part-time groundskeeper for $8.25 an hour.

“If I didn’t show up,” he quipped, “I would have gotten fired and lost my job.”

The honesty of bartenders Patti Rooney and John Marnell.

At the time, Illinois was not part of the Powerball system, so after traveling to Wisconsin to buy tickets for about 10 bar patrons, Rooney and Marnell inserted roughly $200 worth of tickets in envelopes designated for each patron. When media coverage emerged that the winning ticket had been purchased in the business where they had gone, and around the time they had been there, Rooney and Marnell suspected that the winner was lurking in one of those envelopes.

Though many would be tempted to sniff out, then switch out, the 80 million-to-1 odds-defying ticket and claim it as their own, they didn’t pull any such shenanigans. When Capaci unsealed the envelope at the bar that Thursday afternoon, he discovered that he was the winner.

Not long after this storybook start, however, the story came crashing back to earth. Stories about the dark side of lottery winners are numerous — including those in which the newly rich squander their fortune as well as other bleak plot twists that descend into murder.

Fortunately, this story didn’t spiral into something nearly so sinister. But Frank Capaci was unable to keep the euphoric pledge that his friendships “will never disintegrate.” The foreshadowing came early, in the closing paragraphs of my story (headlined “Bartender set table for winner”) that accompanied the light-hearted sidebar that included a vision of Old Style cans stretching across America:

“Next come some delicate questions: Does Capaci share a portion of his new wealth, and if so, with whom and to what extent?

For Tony Capaci, 26, the youngest of the winner’s three sons, Thursday night’s jubilation has been diluted as those sensitive issues came more sharply into focus.

He described Rooney and Marnell as `extremely good friends’ of his parents and said the family `will have a meeting later on next week, when we will end up discussing Patti and John, the whole nine yards.’

Rooney and Marnell, he added, `are truly an asset – they’re an asset to the human race, (for them) to be that honest.’”

Alas, by the end of 1998, Rooney and Marnell claimed that Capaci had reneged on a promise to give them $500,000. Rooney said that Capaci also promised her a house, a car and cash. By that point, he had been banished from the bar after telling Rooney that he had no intention of giving the $500,000.

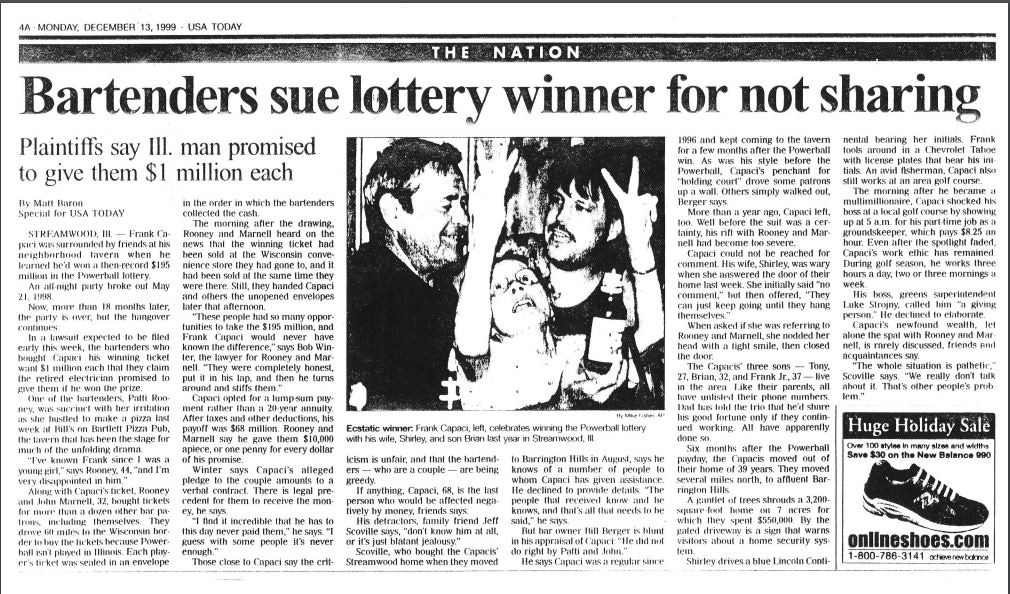

About a year later, they filed a lawsuit claiming that Capaci had broken a promise to give them $1 million each, a development that I broke with a feature for USA Today.

“I’ve known Frank since I was a young girl and I’m very disappointed in him,” Rooney told me.

Her attorney, Robert Winter, described Rooney and Marnell, as “completely honest…and then he turns around and stiffs them.” By contrast, Capaci’s friends and supporters of described him as generous and said the lawsuit stemmed from jealousy.

When I knocked on the door of the Capacis’ new home in a nearby town, Frank’s wife, Shirley3, initially told me she had no comment. Trained to diplomatically allow someone to expand on a “no comment,” I remained at the door long enough for Shirley to offer another remark directed at Rooney and Marnell:

“They can just keep going until they hang themselves.”

Nope, this was no fairy tale anymore.

Four years later, the case was settled for an undisclosed sum. Thereafter, the only public remarks of Capaci that I have found came in the Feb. 17, 2008 edition of the Wisconsin State Journal, six years before his death, on the 20th anniversary of the Wisconsin State Lottery:

In retrospect, it’s clear that the Capacis would have benefited from anonymity — an option that is increasingly available across the country for lottery winners4.

Of course, there is no guarantee that it would have prevented the personal acrimony and litigation that ensued. But you can safely bet that being able to process the situation, and navigate the rest of life, in private would undoubtedly have been preferable to the public spat that played out.

Do you buy lottery tickets? If so, how often? I can count on one hand the number of times I have done so. Also, if you want others to read The Inside Edge, don’t leave it to chance — simply share this and/or other columns with them.

Capaci opted to receive all the money right away in a lump sum — $104 million. Of that total, he received somewhere in the range of $54 million to $67 million after taxes. (Both data points were included in coverage at various times.)

At the time, all media coverage noted he was 67. But his 67th birthday wasn’t until July that year. Just setting the record straight here.

Shirley Capaci is now 87 years old. Frank passed away in 2014, at the age of 83.

As of late 2022, of the 45 states that participate in Powerball, 19 (including Illinois, which joined the Powerball network in 2010) allow winners to remain anonymous. Among those that do not: Wisconsin, where Capaci’s ticket was purchased.

Great story Matt.. musta been fun covering that saga... lotsa lessons to be learned.. I drank in a bar like that.. ya can't shoot your mouth off and play the big shot, and then reneg, without it coming back to bite ya...

Great, fascinating story. Well, Rooney and Marnell might feel differently... but otherwise...