Probable bobble

The Wall Street Journal marveled at a "remarkable quirk" embedded within LeBron James' career statistics. But my research of other stars' stat lines suggests he's the rule, not the exception.

The NBA playoffs are upon us, so I’m in an especially hoops-minded mood.

For those who know my background as a sportswriter, and as a stats columnist, you know what this means. Ready to go down a few statistical rabbit holes?

Sports fanatics won’t need encouragement to stick with this one, but if that’s not you, what follows is really an exploration of probability—specifically when multiple variables are at play.

A simple example: the likelihood of a coin toss resulting in heads one time is 1/2. But three times in a row? That’s 1/2 x 1/2 x 1/2, which equals 1/8th.

Likewise, if Outcome A is likely to occur 1/15th of the time, Outcome B 1/10th of the time and Outcome C 1/10th, then the chance of A and B and C all happening at the same time is the product of those independent variables—once out of 1,500 times (15 x 10 x 10).

These mathematical musings tie back to an article that appeared a few months ago in The Wall Street Journal about what it referred to as a “remarkable quirk.” It was alluding to all-time basketball great LeBron James and how he had never precisely attained 27 points, seven assists and seven rebounds in any single game, despite those figures being his career average over a 21-year career.

To the WSJ’s credit, in his reporting Robert O’Connell pointed out that—as can be attested by anyone who’s done a parlay wager (betting on three different outcomes)—this phenomenon is hardly mind-blowing.

From O’Connell’s story:

“Brian Macdonald and Shinpei Nakamura-Sakai, a data science lecturer and graduate researcher at Yale University, calculated that the chances of James failing to tally that exact line, this deep into his career, were slim but hardly nonexistent: about 27%.”

Even before reading the story to see if they’d included that kind of calculation, I decided over the last few weeks to embark on my own numbers-crunching odyssey.

First, I fact-checked the story by reviewing James’ game-by-game box scores on Basketball Reference, starting with his rookie season.

He’s come close to nailing that trifecta a handful of times. For example, on three occasions he’s had seven assists and seven rebounds but narrowly missed on points by one: Nov. 27, 2004 (26 points), Dec. 12, 2008 (28 points) and April 9, 2013 (28 points).

In the end, though, I confirmed what the newspaper had reported: nary a 27-7-7 game in James’ catalogue. That got me to wondering: How unusual is this?

What if I looked up other longtime NBA stars, each of whom has played over 1,000 games, to see if they ever hit these three statistical averages in a given contest?

Sort of randomly selecting players, I began with an active player, Russell Westbrook.

He’s played 16 seasons, including two with the Los Angeles Lakers as James’ teammate. Westbrook’s averages through 1,162 career games: 22 points, eight assists, seven rebounds.

My finding: Westbrook’s never had a game with exactly those figures. In March 2014, he twice nailed his rebound and assist averages and came close on points (20 in one game, 23 in the other).

Next up: the late, great Kobe Bryant, who played 1,346 games in his Hall of Fame career, all with the Lakers. His averages: 25 points, five assists, five rebounds.

My finding: Bryant never did it, either, in any single game.

He’d come close once, maybe twice in a season, including three occasions (April 20, 1999; March 16, 2001; March 27, 2007) when he was one or two points off from 25 points while snagging five boards and dishing five assists.

And in 2008, the man known as “Black Mamba” improbably had five assists and five rebounds on three occasions in a five-game stretch. But in those games, he tallied 29, 34 and 20 points.

At this point, I began wondering if I’d find anyone who hit their career averages in a single game. Having begun my quest with Westbrook, who had four seasons in which he averaged double figures in all three categories (known as a “triple double”), I thought of the original “Mr. Triple Double,” Oscar Robertson.

Accomplishing something nobody else came close to until Westbrook, Robertson had averaged a triple double his first two seasons over 60 years ago, back before “Triple Double” even emerged as something to pursue. And he’d likely have done it for each of the next three seasons, had society become so stats-obsessed back then.1

Robertson’s career stats: 1040 games, with averages of 26 points, 10 assists and eight rebounds.

My finding: Robertson never had a 26-point, 10-assist, 8-rebound game.

Twice in a two-year span, he came Big O-so-close, with 26 points, 10 assists and seven rebounds on Jan. 16, 1969 and 26 points, 10 assists and nine rebounds on Nov. 11, 1970.

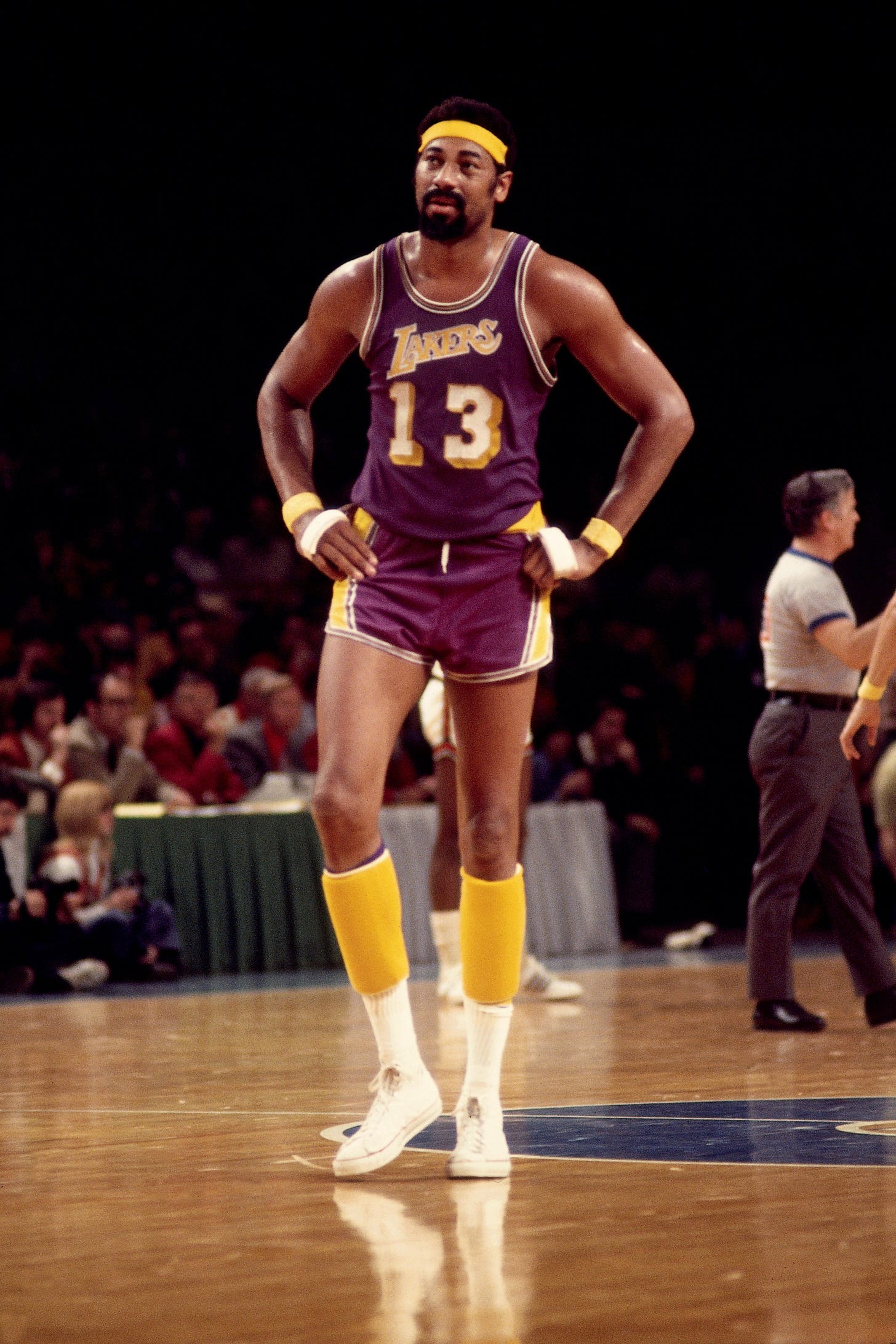

Next, I thought I’d take a look at Wilt Chamberlain, the great center with eye-popping statistics for his entire career from 1959 to 1973.

In that span, Chamberlain played 1,045 regular-season games and posted averages of 30 points, four assists and 23 rebounds.

It didn’t take long for me to see that, at last, I found a match.

In the 42nd game of his rookie season, on January 19, 1960, Chamberlain had 30 points, four assists and 23 rebounds2 in a 114-93 victory for his Philadelphia Warriors over the New York Knicks. Instrumental in making that happen: the notoriously bad free-throw shooter missed seven of his nine free-throw attempts.

Interesting to note a few details from this story in The Philadelphia Inquirer:

#1) This was the first time in his fledgling career that The Big Dipper had been held scoreless in any single quarter.

#2) Fellow rookie center Joe Ruklick helped pick up the slack for the Warriors by scoring 14 points, the second-highest total of his three-year NBA career. In 1990, Joe and I were classmates at Northwestern (he had gotten his bachelor’s degree over 30 year earlier and was back to get a master’s degree; aptly enough in light of this column, we took a research methods for journalism class together.)

As for Chamberlain, he didn’t repeat the 30-point, four-assist, 23-rebound line over his subsequent 1,003 regular-season games, posting some of the most wildly varying stat lines in NBA history.3

I’ve yet to subject other longtime NBA players’ careers to a game-by-game data inspection along these lines. Maybe, in time, that will come.4

However, given the 1-for-5 outcome of this admittedly-small-sample-sized bunch, I think it’s apt to quote another portion of O’Connell’s story:

“In the twilight of his playing days, James has talked about his wish to own an expansion NBA franchise in Las Vegas. His own career would make for a good lesson in the gambling capital of the world: Stay away from combination bets that require too many outcomes to break right.”5

Robertson came up just short with 9.5 assists in his third season, then 9.9 rebounds and 9.0 rebounds, respectively, in his fourth and fifth seasons.

At the time, Chamberlain’s averages were 37 points, two assists and 29 rebounds. It would take him another 13 years before settling in at his final stat line.

For example, in contrast to his legendary 100-point game in March 1962 (when he made 36 of 63 shots from the field and 28 of 32 free throws) Chamberlain scored one solitary point in the last two games, combined, of his career. Despite playing 94 of those games’ 96 minutes, Chamberlain took only one shot from the field, which he missed, and made one of two free throws.

In the history of the NBA, 149 players have appeared in 1,000 games or more. I don’t anticipate digging that deep.

One more thing to keep in mind: With James still active as a player, there’s a legitimate chance his career averages shift from their current figures. His rebounding average is 7.497, so just a little more rebounding and he rounds up to eight per game. And his assist average is 7.38, so rounding up to eight in that category is not beyond his reach, either.

I would have been with the WSJ journalist and would not have guessed the essential slipperiness of this at first blush, although of course it computes if you think about it. Having to hit all three categories and not two is I think what makes it more unlikely than it first seems. Ironically, I think Chamberlain was the most unlikely of the players you sampled to have a matching game, since he got so many rebounds on average. I am operating on the assumption that the higher an average, the higher the standard deviation, and the harder to match.

It's only two categories, but we are sometimes informed that an 11-7 score in the NFL is the first in history, or some such combination, and that is what I am reminded of.

A couple of other brain teasers as I sort this out for myself....if we took some other combination besides the average, particularly in games where the player played a full complement of minutes, the probably of finding a match would decrease. Yet, for a player to be above or below his average in all three categories, is probably at worst only a 1 in 8 proposition, since each individual over/under is just 50%. It is the precision which makes a match unlikely.

The total number of unique pts/rebounds/assists games for a player in his career would also be fun to look at, and probably not too hard to get. This could also indicate what is possible/likely as far as combinations other than the average in each cropping up.

Also might be fun to ask something like, again, assuming a certain number of minutes, what is the probability of a James threesome beating a Chamberlain in all three categories? Or to take two seemingly mismatched players, and ask that question? (Actually, this and other exercises could get tedious after a while.)

Matt, First off I am not a stats guy but I appreciate how you explained this and made it accessible even interesting and folded in some gambling education even. You have many gifts! Okay a stupid question. Are you taking the average over games and working backwards to see if those stats were achieved in any game? It seems to me to be fair you would have to do this iteratively to be fair, starting at the second game. At your first game you would by definition achieve your average as there is only one game. So all players hit their career average at game one. If game two had those exact same stats the career average is met again. And so on. So it would be possible to hit your average at every game along the way with that fact swallowed up and invisible a game later in ones career. Again I am not a stats person but is my thinking correct here? Apologies if this keeps you up at night for years as running every player and every game iteratively to see if an average was achieved will be a lot of computation!