Strolling to a goal

Best known for his base-stealing dominance, Rickey Henderson also mastered a vital ingredient in that pursuit: drawing walks. In 2000, I wrote a feature about this underappreciated, low-key skill.

A week ago, along with just about every other sports fan, I was shocked and saddened to learn of the death of Major League Baseball Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson. As so many have recounted over the years, and especially in the last week, the 65-year-old Henderson was a genuinely unique character in addition to being an extraordinary player.

I never met this man who was most noted for shattering the single-season and career records for stolen bases. But in 2000, I had the opportunity to write a feature story about his pursuit of another career record—drawing walks—that was a key factor in his base-stealing prowess.

I am continually on the look-out for these types of milestone moments, such as crunching data in unique ways on players like Albert Pujols or Miguel Cabrera as they reach the 3,000-hit mark or commemorating the 20th anniversary of Mike Schmidt’s remarkable 1980 season for the Philadelphia Phillies.

In 2000, Henderson was nearing the end of his 25-year Major League Baseball career, while I was a year into what would prove to be my own 25-year freelance journey. At the time, my main bread-and-butter was writing for the Chicago Tribune, but I also pitched stories to other publications.

One was The Seattle Times, as Henderson had been signed by the Seattle Mariners in May, six days after being released by the New York Mets.

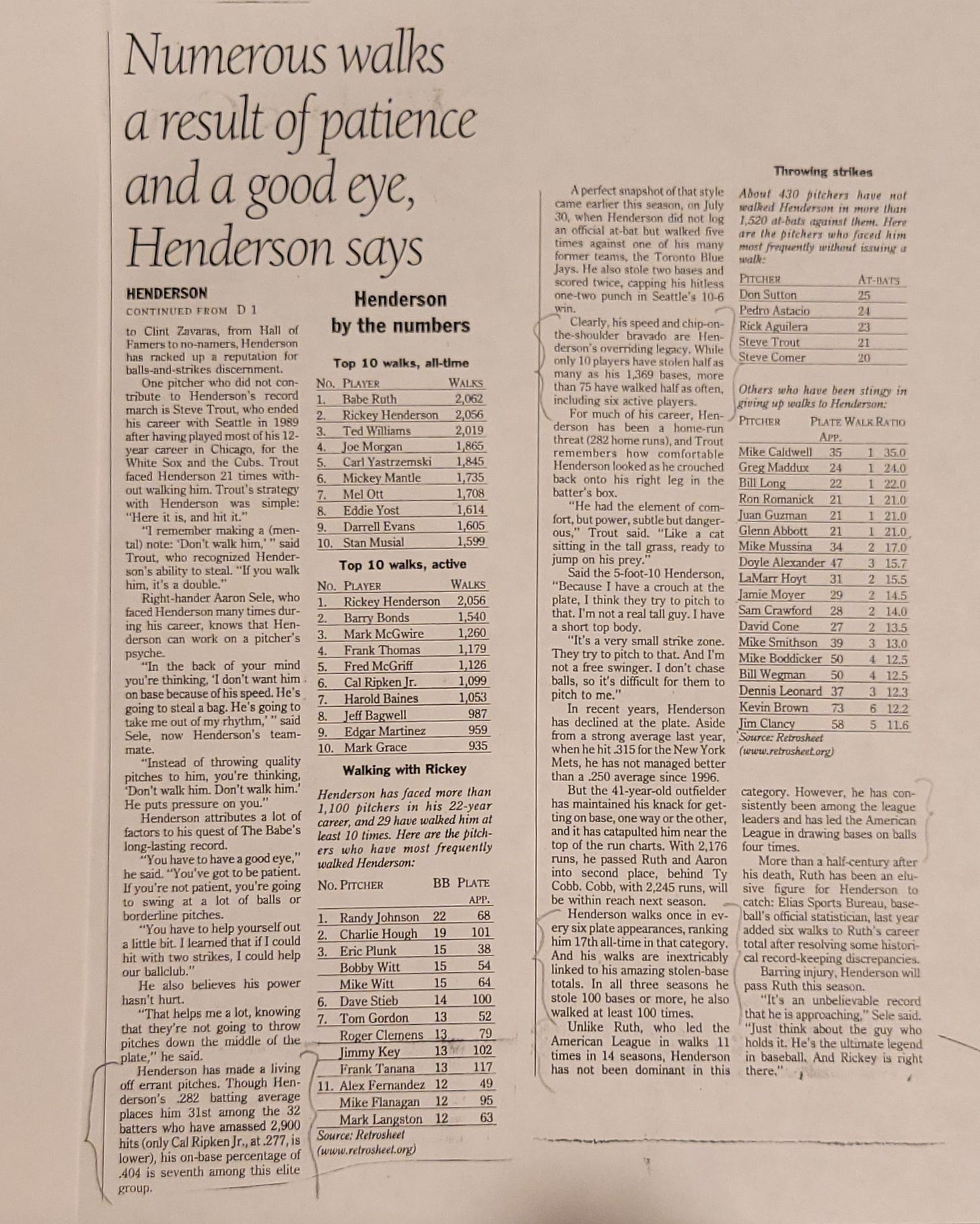

Thanks to one of my favorite resources of all-time, Retrosheet.org, I had been able to drill down on Henderson’s path to this quietly historic moment, so the newspaper’s sports editor gave my story the thumbs-up.

To supplement the stats I’d assembled, the Mariners beat reporter for the paper gathered quotes from Henderson and one of his teammates, pitcher Aaron Sele, while I tracked down Steve Trout1, a retired pitcher who had somehow managed to avoid walking Henderson through 21 plate appearances.

“If you walk him,” Trout told me, “it’s a double.”

The Times did a terrific job designing the story, highlighting among other things the statistics related to Henderson’s patience in drawing bases on balls against various pitchers. My one peeve about the newspaper’s editing of my story: rather than keep my conditional “Henderson could break the record by season’s end” phrasing, the final version portrayed it as a certainty.

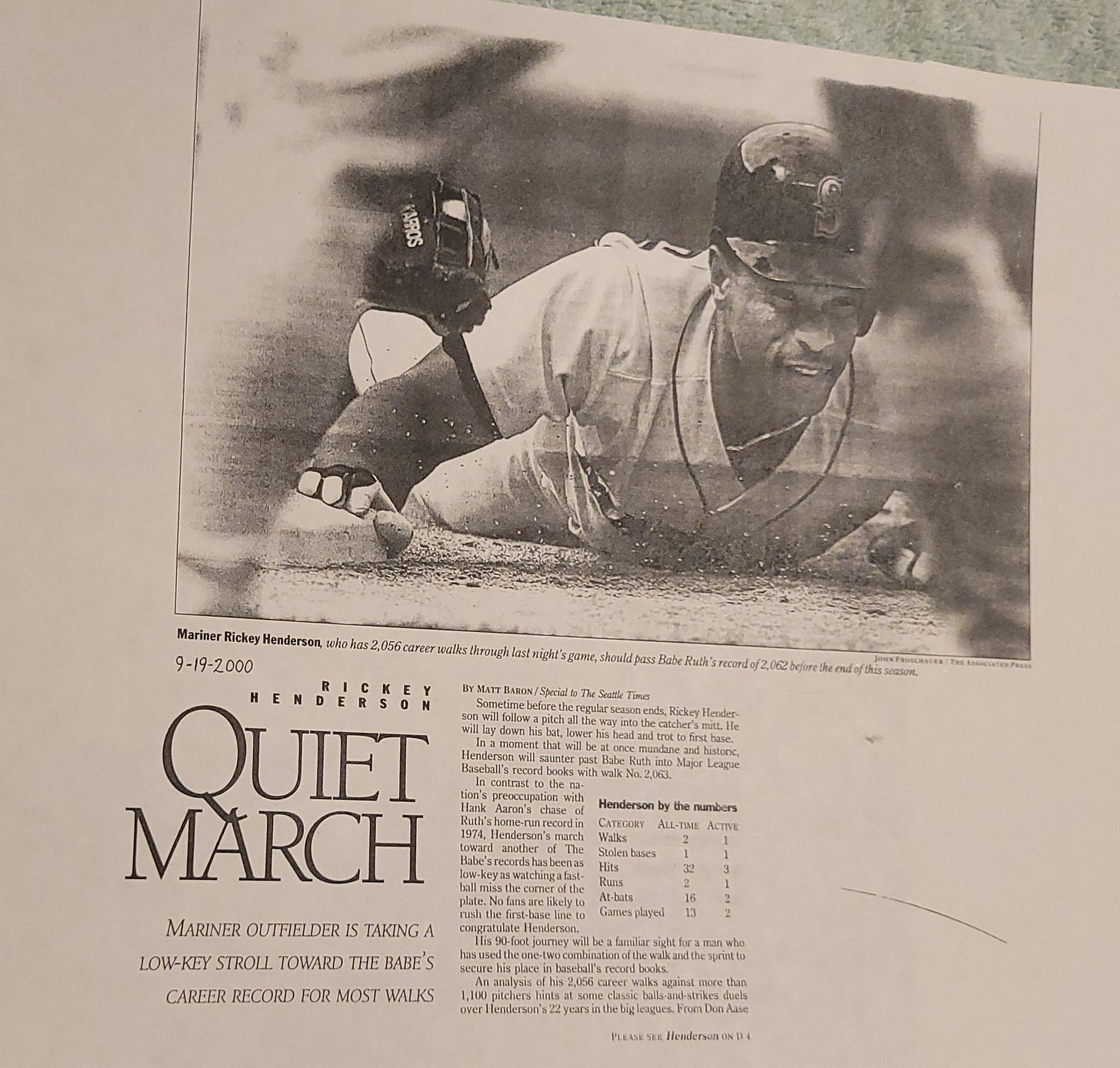

“Sometime before the regular season ends, Rickey Henderson will follow a pitch all the way into the catcher’s mitt. He will lay down his bat, lower his head and trot to first base.”

The future is never that clear.

As it turned out, Henderson walked only four times in the team’s final 12 games, bringing his total two shy of Babe Ruth’s record 2,062 walks. He strolled past Ruth the following spring, as a San Diego Padre, and finished his MLB career two years later with 2,190 walks.2

Of all the tributes that I’ve read about Henderson this past week, the one that stands out the most was referenced by Lincoln Mitchell in his “Kibitzing with Lincoln” column:

While Henderson was playing, there was a narrative around him that he was selfish and kind of goofy. He referred to himself as Rickey, famously framed, rather than cashed a check for $1,000,000 from the Oakland Athletics and frequently forgot the names of his teammates. Those stories always bothered me. The racist undertone was tough to miss, but then after he retired, other stories emerged.

Henderson’s caring spirit, particularly when it came to distributing post-season and World Series shares, revealed that he understood and cared about people.

Mike Piazza described this in his 2013 memoir. “Rickey was the most generous guy I ever played with, and whenever the discussion came around to what we should give one of the fringe people — whether it was a minor leaguer who came up for a few days or the parking lot attendant — Rickey would shout out “Full share!” We’d argue for a while and he’d say, “Fuck that! You can change somebody’s life!”

Rickey Henderson, like everyone else, was obviously much more than numbers.

My interview of Steve Trout led to a 10-week stint co-hosting his radio show, The Rainbow Hour, in early 2001. The studio for the tiny station was an apartment in Berkeley, Illinois and we had some fun, memorable times, including a trip to New York City for the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) banquet.

Henderson’s record was obliterated the year after his 2003 retirement.

That’s when pitchers increasingly wanted absolutely nothing to do with throwing a pitch anywhere close to the plate against Barry Bonds, who zoomed past Henderson’s record. Bonds’ 232 walks in 2004, including 120 intentional walks, remain records that appear insurmountable.

In light of Bonds’ well-established performance-enhancing drug use, however, his base-on-balls dominance are not nearly as controversial as his single-season and career records for home runs.