`You want to talk to a player?’

Bobby Knight's death triggers dueling personal memories: a gentlemanly Knight after a 1988 loss to Northwestern University, and an otherwise-gentlemanly Bill Foster bullying me after a Wildcat loss.

“You want to talk to a player?”

This is the question shouted by Bill Foster, the basketball coach at Northwestern University, as he practically pounces on me and grabs my arm.

Standing outside the team’s locker room, I am caught off-guard. Between Foster’s rage and my own ambition as a 19-year-old reporter, I don’t feel like I have any choice but to say “yes.”

The Wildcats are in the visitors’ locker room at Ohio State, which had just pulled out a surprisingly narrow victory over the struggling NU squad in February 1988. The team’s locker room is typically off-limits to the media, so here’s a chance to get some exclusive quotes.

“You want to talk to a player?”

Although Foster had phrased it as a question, it’s a marching order. He’s still worked up about a question I asked minutes earlier during a press conference. Now, he’s begun perp-walking me, hand tightly wrapped around my arm, like a defendant getting hauled into court.

When we get inside the locker room, I can see the players are getting dressed after showering. It’s now time for my dressing-down. My audio recorder isn’t rolling, but here’s the gist of what Foster says over the next 20-odd seconds:

*He resurrects my press conference question.

I had prefaced it with an observation that Ohio State’s point guard, Curtis Wilson, had enjoyed success driving to the hoop. (I make the mistake of saying Wilson had done so “all night,” a seemingly innocent choice of words that prompts Foster, in front of all the media, to question what game I had been watching. He counters that he thought his team had defended Wilson effectively nearly the entire game.)

*Foster refers to my status as a reporter for the college newspaper, The Daily Northwestern.

He tells Wildcat players that “you’d think”—those two words I vividly remember—that I’d be someone the team could count on to provide more sympathetic coverage.

During this tirade, I walk away to get some distance from the coach; I stop a few feet away from Phil Styles, one of the team’s key players. He looks about as uncomfortable as I feel.

After Foster’s done saying his piece, I turn to Phil and say, skeptically, “Do you want to answer any questions, Phil?”

Phil looks down, shakes his head and mumbles, “No.”

I’m not about to go around the room to put anyone else on the spot. Embarrassed and confused, I walk out.

Boiled down to its essence: Foster has bullied me.

Frustrated and disappointed by another loss (the seventh of what will become a 13-game losing streak to conclude the season), a person with considerable power has just wielded it abusively on a person with little, if any, power.

A few days later in his office, during an interview previewing the next game, Foster offers a meandering non-apology. He doesn’t use the word sorry but uses justifying language to explain why he had gone off on me. Also, note the setting: He doesn’t do it in front of the team, those young men and college classmates who had witnessed his prior outburst.

At the time, I am just relieved this saga seems to be over and I can focus on covering the closing weeks of the season.

Then & Now

Now, as a 55-year-old who has been in numerous and varied settings where I am the authority figure and in a position of power, it’s clear to me that Foster (58 at the time) whiffed in both encounters. Neither was anywhere close to his finest moment.

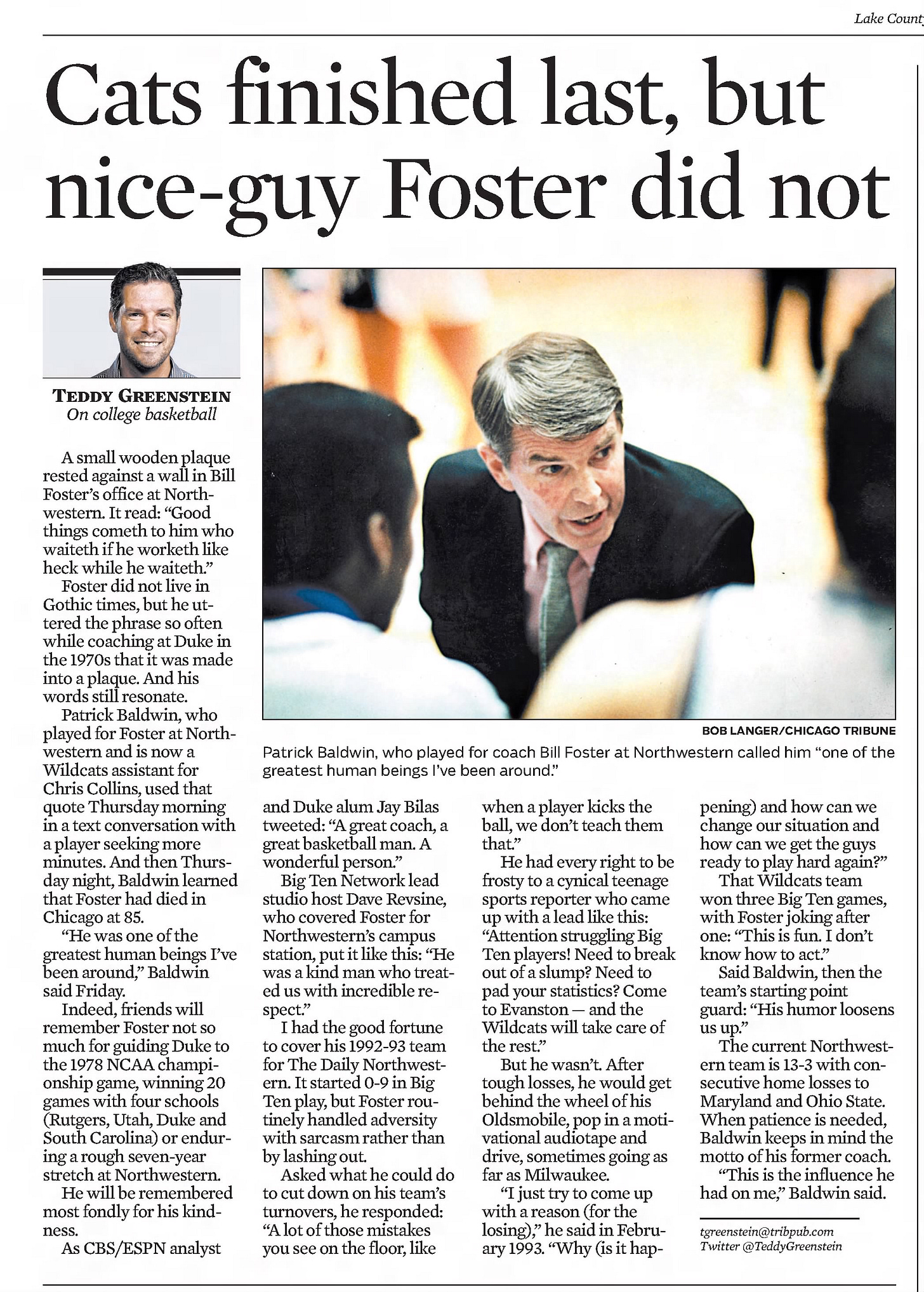

He was in his 25th year as a head college basketball coach; 10 years earlier, he had brought Duke University to the NCAA title game, a loss to Kentucky. He would coach at NU for another five years. Was his behavior toward me an outlier, a rare aberration from a gentlemanly norm? Or was I one of a string of people who were on the receiving end of his bouts of ill temper?

I have no idea. However, I do know that in my journalism career, I cannot recall anyone else unleashing quite that level of fury as Foster exhibited on that winter evening in Columbus, Ohio.

To be clear, I don’t think Foster, who passed away in 2016, was a bad guy at all. As a freshman working in NU’s Sports Information Department and the next year covering the team for The Daily Northwestern, I had numerous interactions with him. Always, he treated me with professionalism and respect.

Me & Bobby

This wasn’t the story I intended to share when I sat down late last night.

I planned to write about Bobby Knight, the longtime Indiana University basketball coach who passed away three days ago at the age of 83.

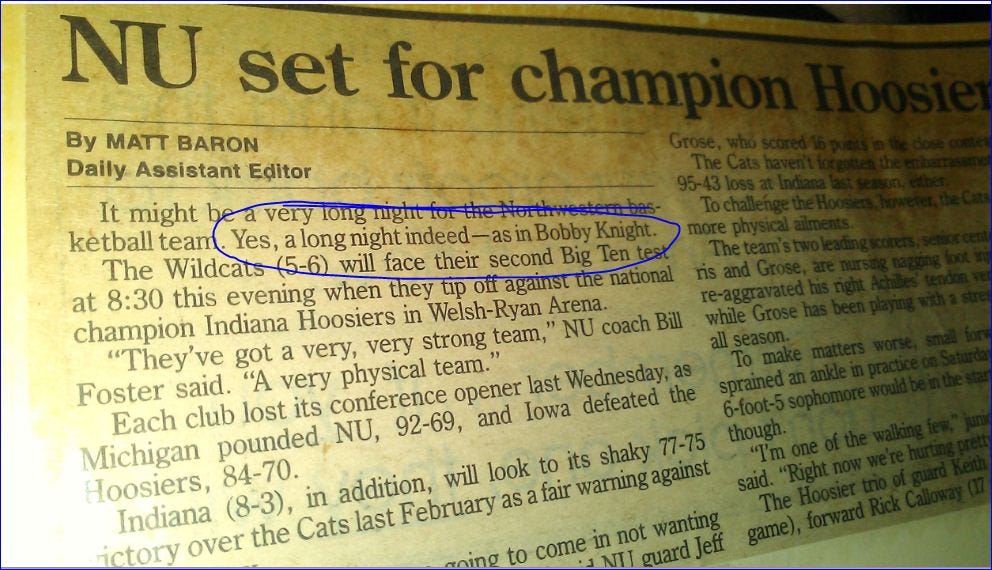

I was going to note, six weeks before Foster’s temper tantrum, that I had written one of my most cringe-inducing ledes before Northwestern’s home game against Indiana, the defending NCAA champion.

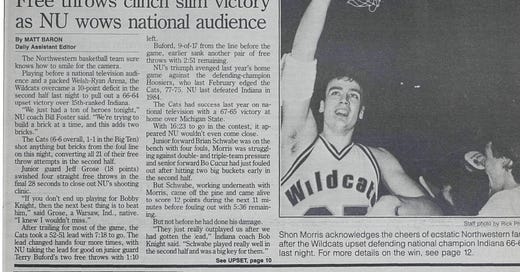

And, of course, I’d then have to mention that NU had pulled off an incredible upset of Indiana, so it wasn’t “a long night indeed—as in Bobby Knight,” after all.

After that stunning victory for the Wildcats, I was one of perhaps six journalists who gathered in front of Knight for post-game comments in the bowels of Welsh-Ryan Arena in Evanston.

First, I saw him, subdued and sincere, congratulate NU player Terry Buford, a gesture that struck me as classy. Then Knight made some remarks before fielding questions.

I wish I could report asking him an insightful zinger that provoked a memorable reply. Instead, well aware of his volatile, menacing reputation1, I kept my mouth shut and simply scribbled, as quickly as I could, as he answered more courageous journalists’ queries.

A month later, in a press conference at IU’s Assembly Hall after the Hoosiers had soundly beaten Northwestern, I took advantage of my second chance to ask Knight a question. Whatever it was, I have forgotten it, along with the details of Indiana’s 74-45 romp that night.

Only nine days later came Coach Foster’s post-Buckeye loss meltdown.

As I read stories of Knight’s career and life—the whole Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde stuff, how you “either loved him or hated him”—the memory of Foster channeling his inner Bobby Knight flooded back.2

For Knight, there was the extremely good (including three national championships, a U.S. Olympic Gold medal as coach of the 1984 team, and testimonies from people about his thoughtfulness and care), there was the horribly bad, and there was the certifiably ugly of his thoroughly documented life.

One story, from September 2000, is relatively bland. But it would prove to be the tipping point that ended Knight’s 29-year tenure at Indiana University. The broad-brush strokes include a 19-year-old asking Knight (then 59) a question that offended the coach, who grabbed the teen by the arm while chewing him out.

Sound familiar?

As ESPN.com reported at the time:

“(Kent) Harvey and his brothers -- Kyle and Kevin Harvey -- and two friends were at Assembly Hall on campus in Bloomington to pick up football tickets. Kent Harvey and Knight passed each other at a doorway.

Kent Harvey greeted Knight with, “Hey, what’s up, Knight?” That prompted Knight to grab his arm and admonish him.

“I said, `Son, my name is not Knight to you,’” Knight said Friday. “It’s Coach Knight or it’s Mr. Knight. I don't call people by their last name, and neither should you.’”

The incident was the last straw that resulted in Knight’s ouster from IU. After years of boorish behavior and on the heels of a recent revelation of his physical assault of one of his players, Knight was on thin ice—a “zero tolerance” agreement had been put into place by the university months earlier.

So, if it had not been his reaction on that day, then I believe it would have been something else on another day not far into the future. Just the same, the common threads between Knight’s response to the IU student and Foster’s response to me are eerie.

A big chunk of my background knowledge of Knight came via John Feinstein’s book, “A Season on the Brink,” an intimate chronicling of Indiana’s 1985-86 season. I knew of Knight’s penchant for bullying reporters. Even when he behaved like a pussycat around me, I didn’t take the bait.

Perhaps it’s fitting that Ohio State is where Knight played on a team that won one national title and was runner-up twice.

Matt: Olympic coaches do not win Olympic medals, even if they coach Olympic champions. Medals are NOT awarded to coaches. Bob Knight did not win an Olympic Gold medal as a coach ... his team did.

I always thought sports writers and commentators walk a thin line between "objectivity" and being a "homer" or "fan." When I was a kid I resented Mel Allen - the voice of the Yankees - because among other things, he was such a "homer."

I loved Steve Stone, because as Cub analyst he was so knowledgeable that he often predicted the next play. He was the opposite of a "homer" ... the consummate expert - he really was - and professional. But the Cub players deeply resented him because he "called it like it is" and showed no favoritism. Apparently I was not the only "fan" who appreciated Stone's professionalism ... but he paid a price for that.

These days - sports, even at the collegiate level - is somewhat different than when you were reporting. It is a multibillion dollar business and now there is no charade pretending it is not. So big bucks are on the line. In such a situation the athlete, the coach, the "institution" I would think has the advantage and the little ole sports journalist better be careful. Then again, maybe not. After all the DAILY NORTHWESTERN did take down Coach Fritz.

The question is can you be a beloved sport's journalist afraid of no one - an icon - and still tell it like it is and not get fired or cancelled? Vin Scully comes to mind.