Attitude of gratitude

Tim McCarthy, my father-in-law, died two days ago. He didn’t dwell on fractured relationships. Instead, he was a master at focusing on the blessings in his life.

For no apparent reason, I woke up about 4:30 a.m. Thursday—and, miracle of miracles, I stayed up.

Weighing heavily on my mind was my father-in-law, Tim.

In declining health for months, he had just been admitted to a hospice care facility. The end was near.

The night before, Bridgett and I had spoken to him over the phone. A man of many words throughout his life, Tim couldn’t speak but took in our remarks, an aide said.

Three hours after I’d risen, Bridgett was awakened by a phone call and came downstairs, surprised to find me at my computer working. Her dad had passed away at 4:32.

Right to the very end, Tim and I had a special connection.

Our closeness came despite Tim’s developing into an outcast in his own blended family that includes three daughters and three sons. He was a pariah held in disdain, kept at arm’s length, barely tolerated at weddings and other rare family gatherings where he’d secure an invitation.

And it wasn’t as if Tim was an innocent victim. As he would often acknowledge in his later years, he was a terrible dad for many years. He was an abusive alcoholic until he stopped drinking in his 40s; for many years beyond that, his neglectful and narcissistic patterns persisted.1

But we always got along, a direct result of Bridgett resolving to honor him despite his failings. I took my cue from her.

A charming, charismatic salesman from what I know of his earlier years, Tim was something of a nomad from the 1990s into the 2010s, living in Mexico and South Carolina and Wisconsin and being out of touch for long stretches. When he’d pop back up in the Chicago area, every year or two, we’d meet him for lunch, or he’d come over for a visit.

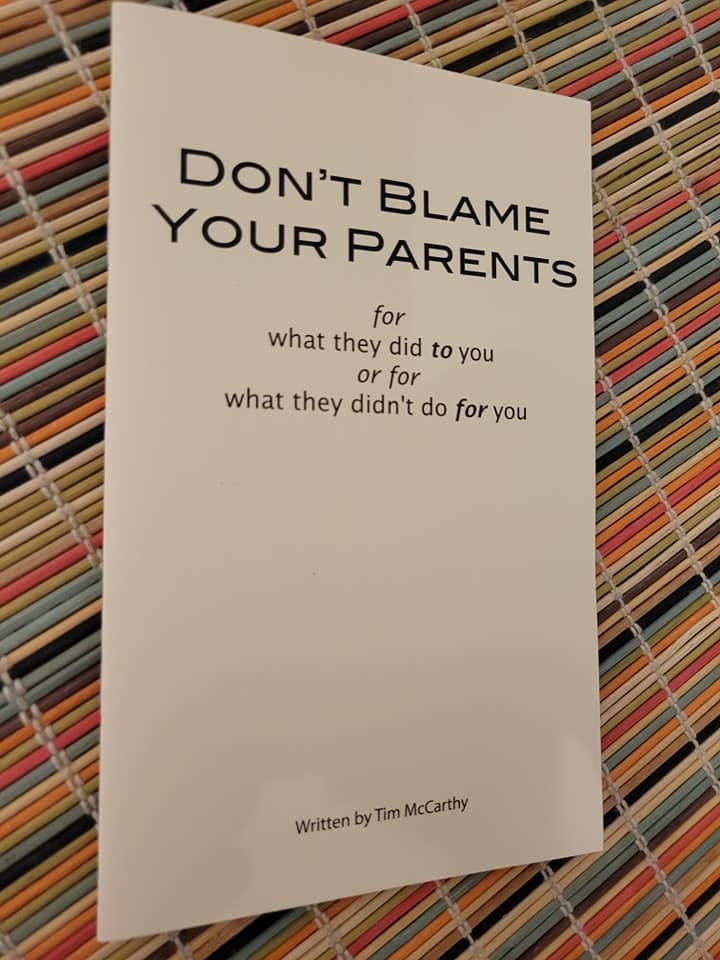

Three years ago, not long after he’d finally settled into his manufactured home near Madison, Wisconsin, Tim enlisted me to edit a booklet he entitled “Don’t Blame Your Parents.”

In view of Tim’s own checkered history as a parent, it had the feel of a defense attorney’s closing statements at trial. I don’t agree with every sentence. But it was also loaded with spot-on wisdom.

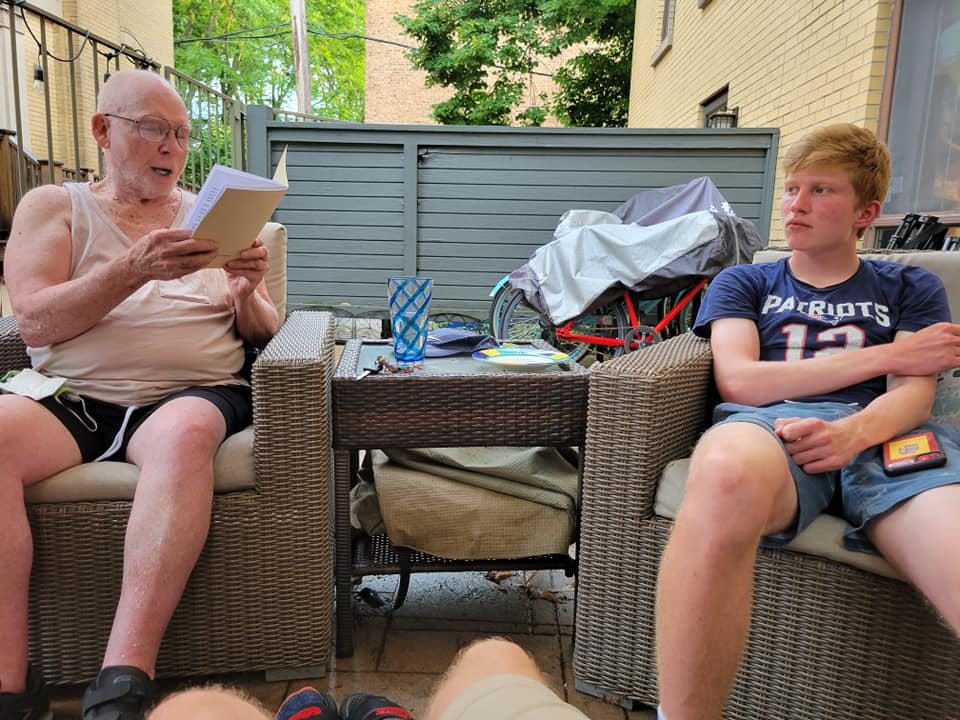

I asked him to read an excerpt to my then-17-year-old son, Zach. I was motivated not only by Zach’s uncanny penchant for blaming his parents, but because it made for one hilarious moment.

Tim later labored over a booklet sequel. He called it “Stupid” —at least, that’s how he labeled the Microsoft Word document that he sent last summer. The full title was to be “Don’t Be Stupid” or “Stop Being Stupid.”

Though “Stupid” never made it to the printing press, I served as editor for that one, too.2

Over the last year in particular, I spent more one-on-one time with Tim, escorting him to his medical appointments at the VA Hospital in Madison, stopping at Culver’s for dinner and swapping stories from our lives. (A sampling, from May 2023, is “The Silence Between the Notes,” below.)

Every single time, he expressed his gratitude for me, for our family, for the nurse taking his blood pressure, for the person who just served him a burger, for just about anyone who crossed his path.

Over the course of his 85 ½ years, Tim McCarthy meant different things to different people, but in my experience, he was the epitome of a grateful human being. He didn’t dwell on the relationships that were fractured or fraught; instead, he focused on the blessings in his life and on the interactions that he did get to experience.

As for my relationship with Tim, it was possible only because of Bridgett.

Here on Easter weekend, as I reflect on Christ’s forgiveness, grace, mercy and love, I also celebrate my wife’s embrace of those principles.

Over these many years, she often didn’t “feel” like loving her dad; particularly when recalling Tim’s earlier years, he wasn’t always that lovable. But she treated “love” like the action verb that it is and was obedient to God’s call to honor her father.

And that love tilled the soil for my friendship with Tim, a gift that I’ll forever cherish.

Not delving into the particulars here, but Bridgett and I have always recognized that those other family members have understandable reasons for keeping their distance.

The first words of “Stupid”: “This world, the one you call home, is insane, it is a colossal and chaotic loony bin. Most people are painfully aware of that.” In the following excerpt, Tim echoes the theme of his first booklet:

“You probably don't take responsibility for the problems in your life. You probably blame the world, other people, or God. And other people blame you for their problems.

Few realize blame is also a drug, available 24/7, self-prescribed and, like any sedative, it's addictive.”

In addition to subscribing to The Inside Edge, you can support my writing for any amount you choose.

One of your best, Matt. I'll be sharing w someone who needs it, a young Mom w difficult mother.

As a biographer I suggest that you "publish " these two booklets on Facebook, using the "Albums" function. It's free, permanent, and I certainly can show you the rudiments.

You might find this big Fbk page interesting: "Parents of Estranged Adult Children -- All Stages".

Matt, I loved this column. Thank you for sharing and for your wife showing how to love in a challenging family