Brother Love, August 2022

Meatball sandwiches, remembering Tupac & strolling the Shakespearean stage

Today comes the next installment of Brother Love, a series of essays about my brother Phil and our relationship. Now 57, Phil’s life has been marked by alcohol and drug abuse and addiction for his entire adulthood.

Those struggles have resulted in yearslong stretches of homelessness, with intermittent periods of housing stability. Fortunately, for the last 2 1/2 years he has had shelter—first for two years at a studio apartment on Chicago’s North side and for the last six months at an even smaller studio apartment in the city’s South Loop.

Previous Brother Love essays can be found in The Inside Edge archives. The most recent one, from a month ago, chronicled a frigid day that I spent with him in January 2022. Below you can access that piece, Brother Love: `The Water is Boiling.’

Today, we fast-forward seven months:

Sunday, August 7, 2022

Phil’s phone can’t make phone calls—he’s let the service lapse again1—but he finds that he can send and receive texts from the Wi-Fi of a Pace bus. So, a flurry of texts brings me to the Forest Park train station, where I pick him up shortly after 1 p.m.

It’s our first time together in exactly three Sundays and the first thing I tell him is he looks good. He’s somewhat surprised, noting that he had just gotten through a bout of illness after unwisely eating ice cream that had melted, then was re-frozen.

“I should have known better,” he says.

First stop is about a half-mile away: Famous Liquors, where Phil gets a great deal on some booze or another. Probably vodka, which is his favorite to mix with soda as he chugs his way through the day. I mention seeing a cart full of wines on sale for $1.99 a bottle. Probably not the greatest quality, I observe.

“Wine,” he responds, “is wine.”

“That’s true,” I answer, unable to refute the air-tight logic.

During his work today at the Oak Brook intersection—“just got soaked in oakbrook the last three hours,” Phil had texted me earlier—a motorist had given him a Potbelly gift card with $25 scrawled on it. So we head over there to the shop where Zach has worked the past three years. Phil tries to figure out how much is actually on the card, but I tell him it doesn’t matter—we can pay any which way.

We place our sandwich orders: a meatball skinny for him, a meatball original for me. Our sandwich maker is Zach’s friend who was instrumental in his getting the job here.

At the cash register, when I present the gift card, it turns out that it covers Phil’s sandwich, but not mine. A most unorthodox path to dining Dutch!

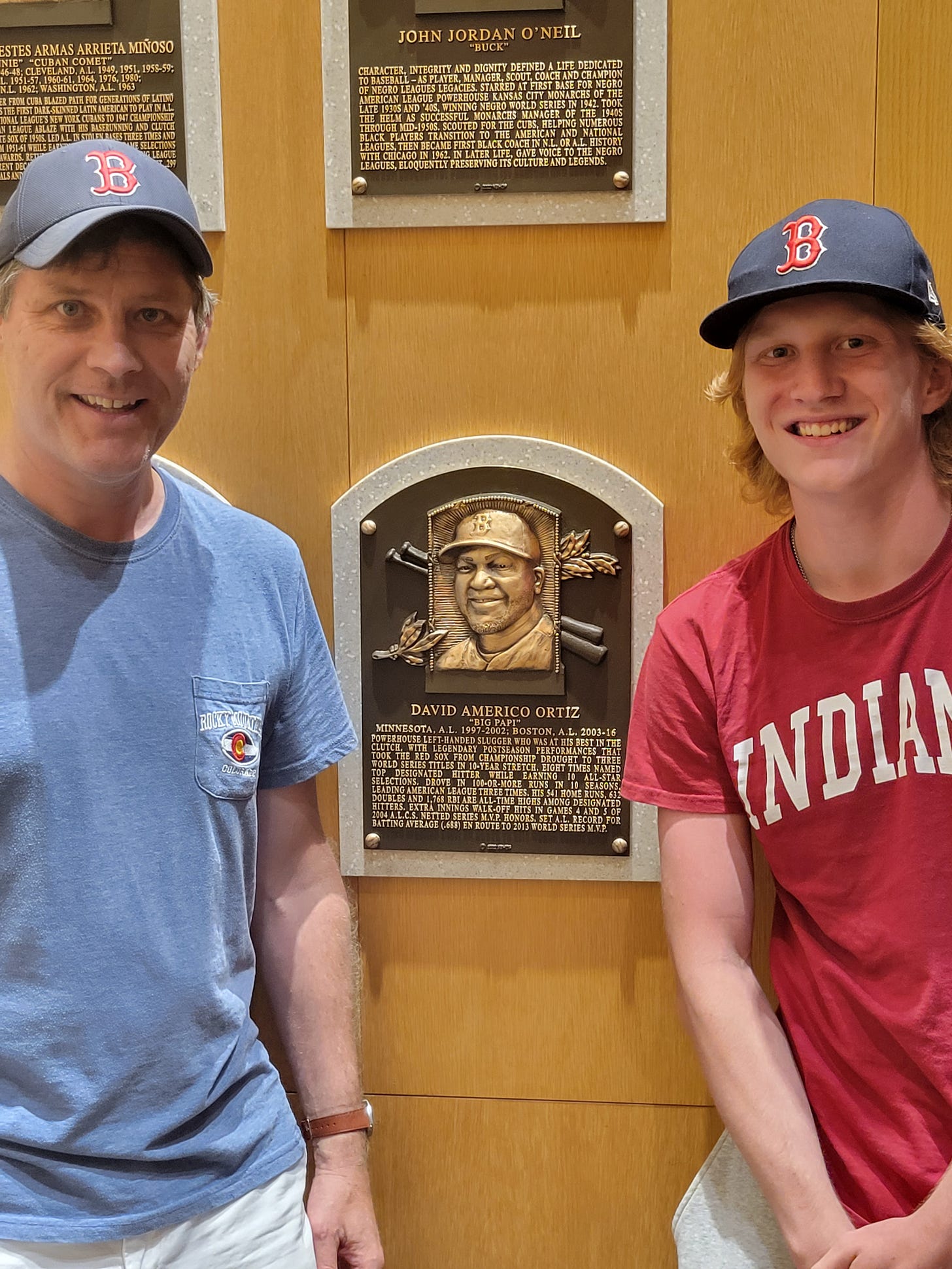

Settled into our booth, I show Phil photos from my trip back east a few weeks ago, including Fenway Park and the two Halls of Fame, both baseball in Cooperstown, New York and basketball in Springfield, Mass. When I mention David “Big Papi” Ortiz and his World Series heroics over the course of three titles, Phil is confused.

“They won three times?”

“Three with Big Papi, and one after he retired, in 2018,” I say, listing the years for each championship: 2004, 2007, 2013 and 2018.

“What’s wrong with me?” Phil says with a tone of befuddlement. “I only knew they had won once.”

I shrug it off. Our conversation turns to other family members, and Phil asks how our cousin Russ is doing. He says he should reach out to Russ but wouldn’t have much to say—certainly nothing in the category of great achievements.

“That’s OK,” I say. “You don’t have to accomplish this or that. We love you just as you are.”

His eyes get misty…the conversation moves onward; with Phil, there’s rarely a few seconds of silence. As always, it’s as if he is trying to cram as much into our time together as possible, given our sporadic opportunities to connect.

“Is our 90 minutes up yet?”

He is quoting the timeframe I had told him that I was able to spend with him. No, we have another half-hour, I say, suggesting we go for a walk.

As we get up to go, a fellow wearing a Tupac Shakur T-shirt comes in to pick up an order. Phil informs him that he was very near the scene where the legendary rapper was killed in Las Vegas. He offers a few details—the police, the emergency lights, the crowd of people nearby.

“This is true,” I chime in. “He was there.”

“Were people crying?” the guy asks.

“No,” Phil says. “It had just happened, and people were trying to figure out what was going on.”2

“I was, like, five years old when it happened,” the guy replies. “I’m 31 now.”

`I Pay a Lot of Compliments’

Out on the sidewalk, a guy about 60 years old with a ZZ top-esque beard and cut-off Boston College sweatshirt strides toward us.

“Nice beard,” Phil says.

Without skipping a beat or slowing down, the man, no doubt used to affirmation of his tumbleweed, replies, “Thank you.”

“I pay a lot of compliments,” Phil comments, going on to explain that you never know what kind of day someone is having and that a few encouraging words—something as simple as praising a woman’s shoes—can help turn around that individual’s day.

He also observes that when someone is cranky toward you, it’s often because someone has just dumped on them—so don’t take it personally.

“That’s great,” I affirm. “You never know what’s going on with someone.”

Walking through a parking lot behind a bank, my memory is triggered: this is the area where an old friend of Phil’s told me he was doing some work this week. He is hoping Phil could work with him, so I dial him up and put Phil on the phone.

“Hi Billy… yeah, I’m still going out to the place in Oak Brook… it’s humiliating...”

After talking for several minutes, Phil jots down notes on his hand about a rendezvous spot the next morning in Chicago. I offer a scrap of paper, which he uses to rewrite the notes, as well as his friend’s phone number—at least the third time, in 2022 alone, that I have provided it.

This reminds me: I should have the phone number of the new case worker, Gil, who is overseeing Phil’s apartment stay. This is the third staffer assigned to Phil with the agency that has provided his housing, entirely free, these past 15 months. I get Gil’s number and make a note to contact him tomorrow.

On a call this past week, Phil had told Gil that he was an alcoholic drug addict—a status of which Gil was entirely unaware, according to Phil’s account. In effect, that is a disability, and could help Phil retain his housing, is how Phil describes the situation.

I never know the accuracy of these accounts—hard for me to conceive of the agency being ignorant of Phil’s alcoholism and drug addiction. I really don’t know how much weight to assign any of it. But at least I have a way of reaching Gil to advocate on Phil’s behalf…I hope. I guess I’ll find out tomorrow when I call the number.

Meantime, for Phil, the call with his old friend has apparently opened the door for him to do a day of labor, something that will be an alternative to panhandling. Phil also suspects the pal might want to get a good “drunk” in. Who knows what tomorrow will bring?3

`All the World’s a Stage’

By this point, we have walked over to Austin Gardens, where the stage for a Shakespearean production looms regally on one end of the park.

“`All the world’s a stage,’” I say, in a burst of abject unoriginality. “I think Billy Shakespeare coined that. You know, we made it longer than him. He died at the age of 52.”

Strolling onto the stage, up the backstage stairs, and back out onto the stage, Phil evaluates the quality of the craftsmanship (poor, in his journeyman carpenter’s view). Ever the good sport, when I suggest taking a few photos, Phil strikes a few poses.

After we make our way back to the van, Phil asks if he smells heavily of alcohol. It’s a question he poses to me almost every time we’re together.

“About the same as usual,” is my reply, as I strive for a brotherly blend of diplomacy, accuracy and brevity.

Next, we are en route to the Thornton’s gas station (Phil needs to buy soda) near the Blue line that will take him home. He reminds me not to talk to “any of these cats” who panhandle in the area, except Gambit, whom I’ve met several times and whom Phil trusts.

Once we reach the Thornton’s lot, Phil gets out and grabs his duffel bag and other possessions. “If you haven’t seen me for a few months,” Phil adds, “you can ask Gambit if he knows where I am.”

We embrace. Phil tells me he loves me, then I respond with the words he often uses to one-up me in these moments: “I love you more.”

For the past month, Phil has been without cell phone service (once again), though we have spoken briefly as he’s borrowed a phone in his apartment building to touch base. A few times over the past two weeks, I have driven to the intersection in the western suburbs where he routinely panhandles, but he’s not been around.

One of the subjects I look forward to bringing up when I next see Phil: the arrest three weeks ago of Duane Davis in Shakur’s murder.

As it turned out, amid confusion and miscommunication, things didn’t work out for them to connect the next day, Phil later told me.

My understanding is that contrary to your brother's idea of "disability" the ADA only protects a person in recovery who is no longer engaging in the current illegal use of drugs. And I speculate - but do not know for sure - that many local and state agencies follow ADA guidelines.

See a repetition of the "cramming" theme: before, to get as much drug use in as possible before having to quit, this time to spent as much time with you in an interval as possible. If that isn't actually a dymanic of his, it seems to at least be something in your mind.