Dad & Dillinger

90 years ago yesterday, my dad was born. The same day, John Dillinger led a bank robbery in Montpelier, Indiana. Let's see where these unrelated events might take us.

I am fascinated by the interplay between certain historical events.

Sometimes, they have an intersectional quality — like the fact that my parents conceived my eldest sibling, Judi, on the day that our 35th President, John F. Kennedy, was assassinated.

There’s a lot more to my family’s origin story but suffice to say that there was a cause-and-effect relationship between these two occurrences. Without JFK’s death, there is likely not Judi’s life, nor the lives of the three boys (wrapping up with yours truly) who followed over the next four years.1

Then there are parallel incidents. These are things that happened at, or very close to, the same time but one did not have any influence on the other.

Take August 4, 1933.

On that Friday, 90 years ago yesterday, my dad was born in Quincy, Massachusetts.

And some 900 miles to the west, in a rural Indiana town named after the capital of Vermont (Montpelier), John Dillinger and a few cohorts robbed a bank.

The next day, the Muncie Evening Press put the passive tense into overdrive. First, there’s the barely decipherable headline (“Believe Yeggs in Two Hold-Ups Same Persons”). And then there’s the Yoda-like lede (it’s fun to read it aloud in your best imitation of the beloved Star Wars character):

“Belief that the bandits who held up the First National Bank of Montpelier, Friday, were the same men who three weeks ago held up the Commercial Bank at Daleville was expressed by Muncie police today.”

For those puzzled by the headline, a “yegg” is slang for “burglar” or “robber.” Now that is one nifty Scrabble word to have in your back pocket.

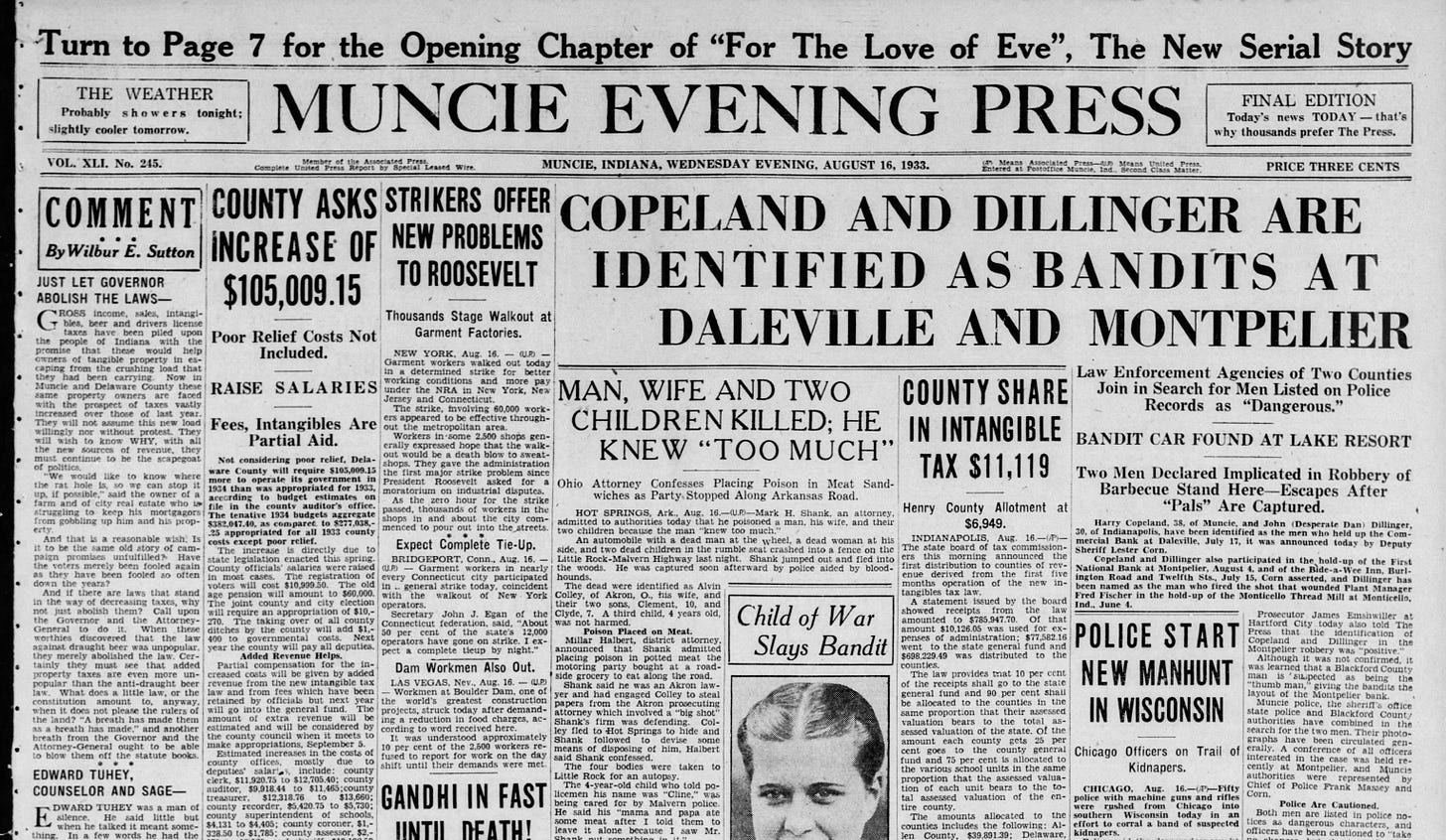

Back to Dillinger and his gang. Their identities started to leak out in short order. Check out the front page from Aug. 16, 1933, which refers to Dillinger’s nickname as “Desperate Dan.” Copeland had to settle for a simple “Harry.”

Certainly, Dillinger robbed banks and committed all manner of bad deeds on many of the 400-plus days between the end of his eight years in prison and the end of his life. He and his gang robbed 24 banks and four police stations during a 14-month crime spree.

Dillinger met his end in July 1934, gunned down by federal agents outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago. He had just seen Manhattan Melodrama, starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, William Powell and a 13-year-old Mickey Rooney.2

That day, movie-goers saw a blizzard of listings on page 54 of the Chicago Daily Tribune. It’s conceivable that Dillinger was among those scanning his options as stars like Shirley Temple, James Cagney, Spencer Tracy and Bette Davis vied for his attention.

The following day, Dillinger’s name was splashed atop the Tribune’s front page, in the largest point size editors could muster. The headline is a blunt three-word piece of staccato prose: “KILL DILLINGER HERE.”

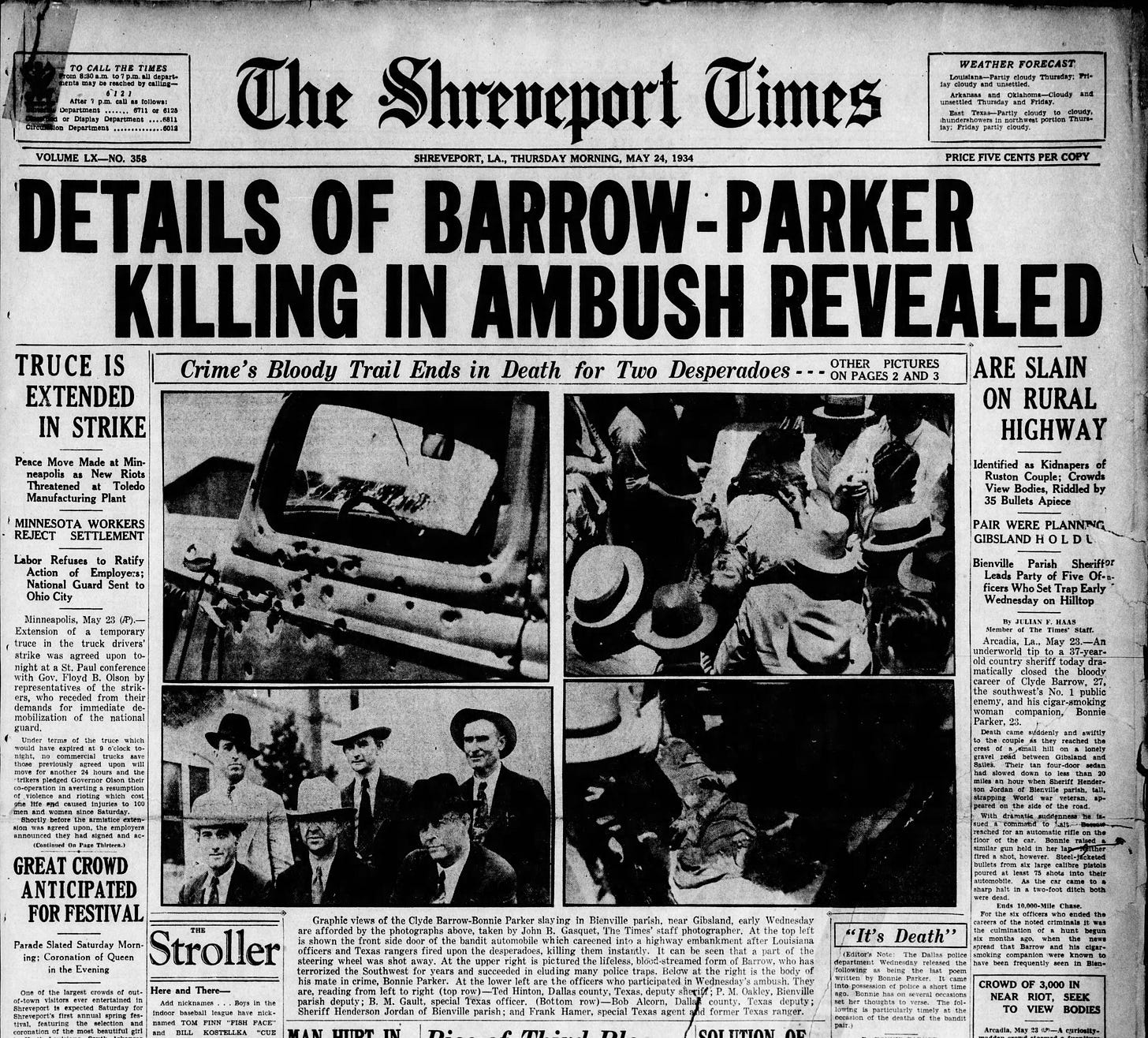

Those Depression-era days are referred to as the “Public Enemy Era,” and with ample reason. For example, Dillinger’s death came just two months after the deaths of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow.

Hunted for months and wanted for the murders of 13 people, including two police officers, they were shot in an ambush dozens of times by Louisiana police officers and Texas rangers in Arcadia, Louisiana.3

Didn’t take much to go down all these bad-guy alleys, so let’s wrap back up with my dad, the baby born near Boston on that August 1933 day.

He made it to nearly 75 years old. Like most people, the biggest headline that Philip Charles Baron commanded came via his obituary. Not long after, my Father’s Day column about our complicated-yet-simple relationship (see my column “A Living Eulogy,” immediately below) appeared in a Florida parenting magazine.

I didn’t mention Dad’s professional life in either of those columns, but now seems the perfect time to do so.

For 41 years, he worked his way up the ladder, from teller to an executive position, at the First National Bank of Boston.

Yes, it’s sort of strange to ponder that I might owe my very existence to Lee Harvey Oswald and any others with whom he might have conspired on that fateful, tragic November 1963 day in Dallas.

Mickey was bound to show up again in an Inside Edge column. He acted in roughly 29,000 movies, after all. Slight exaggeration. If you didn’t read about my interview of him in 2000, you can check it out below:

Me & Mickey Rooney

Of the thousands of people I have interviewed over the course of my journalism career, one of the biggest names also had some of the shortest answers: Mickey Rooney. By the time we spoke, in April 2001, he was 80 years old and had surely been interviewed thousands of times in a legendary entertainment career that dated back to the 1920s. To him, I was ju…

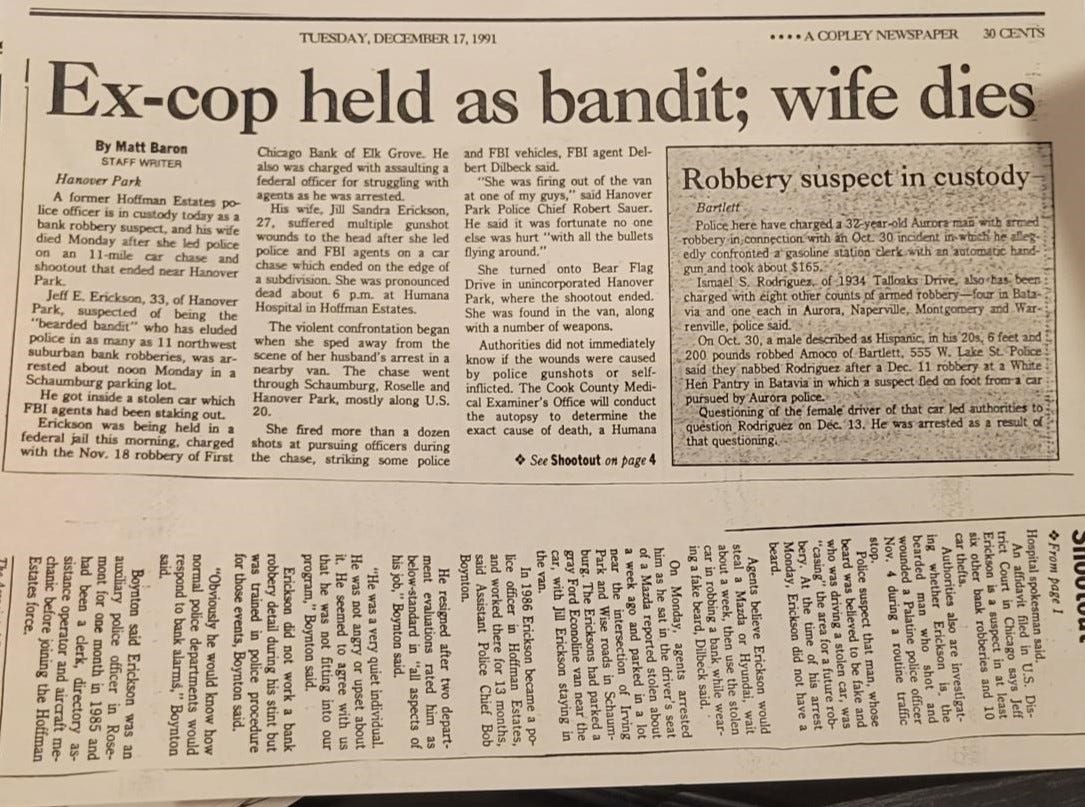

Speaking of Bonnie and Clyde, in December 1991 I wrote about Jeff and Jill Erickson, who were frequently likened in media accounts to that couple whose violent life on the run was most romanticized by the 1967 movie starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. The Ericksons owned a used bookstore that was always closed on Mondays, which was their preferred day of the week to pull of bank heists in the Chicago suburbs.

On Dec. 16, 1991, Jill died of a self-inflicted gunshot during a shootout with police; Jeff died seven months later during an attempted escape. After the sixth day of his trial in downtown Chicago, Jeff shot and killed two guards, then himself after he was wounded by one of the guards.